The content on this page has been converted from PDF to HTML format using an artificial intelligence (AI) tool as part of our ongoing efforts to improve accessibility and usability of our publications. Note:

- No human verification has been conducted of the converted content.

- While we strive for accuracy errors or omissions may exist.

- This content is provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon as a definitive or authoritative source.

- For the official and verified version of the publication, refer to the original PDF document.

If you identify any inaccuracies or have concerns about the content, please contact us at [email protected].

Review of Corporate Governance Reporting 2024

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Code Compliance

- 1. Board leadership and company purpose

- Shareholder engagement

- Stakeholder and workforce engagement

- 2. Division of Responsibilities

- 4. Audit, Risk and Internal Controls

- Audit

- Independence

- Effectiveness of external audit

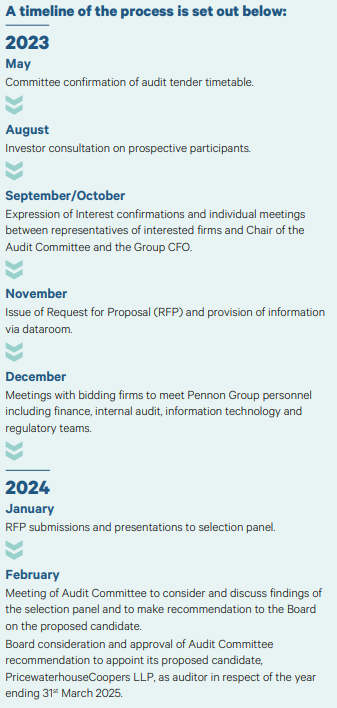

- Tender and tenure of the external auditor

- Internal audit

- Audit Quality Review inspection results

- Risk

- Risk Management and Internal Control

- Board responsibility and assurance mechanisms

- Reporting on the review of effectiveness of risk management and internal control systems

- Reporting on the outcome of the review of effectiveness of risk management and internal control systems

- Viability

- Cyber and Information Technology

- 5. Remuneration

The FRC does not accept any liability to any party for any loss, damage or costs howsoever arising, whether directly or indirectly, whether in contract, tort or otherwise from any action or decision taken (or not taken) as a result of any person relying on or otherwise using this document or arising from any omission from it.

© The Financial Reporting Council Limited 2024 The Financial Reporting Council Limited is a company limited by guarantee. Registered in England number

- Registered Office: 8th Floor, 125 London Wall, London EC2Y 5AS

Executive summary

This annual review of corporate governance reporting has been published as companies prepare to implement the new 2024 UK Corporate Governance Code next year. Our focus has been on showcasing examples of good reporting and exploring areas of improvement to help with those preparations. The 2018 UK Corporate Governance Code (the Code) remains in effect for annual reports in

- Companies will be preparing now for the transition to the new Code, which is applicable for financial years from January 1, 2025. Reporting against the new Provision 29 on the effectiveness of risk management and internal controls will start from 2027. We hope this review will support companies and other stakeholders to navigate these upcoming changes effectively.

Flexibility remains a key feature of the new Code. While the UK Listing Rules require companies to apply the Code's principles, these are written at a high level and allow for interpretation by companies in a way that suits their particular circumstances. Companies can either comply with the provisions or explain their departures. The FRC supports departures from the Code where there is a cogent explanation given, and indeed an explanation can give additional insight into the governance of the company.

This year we found fewer companies chose to depart from the Code. This can be primarily attributed to increased compliance with the Provision related to alignment of pension contributions, where companies have, over the years, been able to move away from non-compliant contracts. When departing from the Code, we would like to remind companies that the explanation should be clear and provide sufficient detail.

This year's review paid particular attention to risk management and internal controls reporting, including a year-on-year analysis of risk disclosure practices. It was encouraging to see many companies did update their reporting over time, particularly in relation to the mitigations put in place to manage their principal risks.

Despite existing requirements under the 2018 Code, reporting on the effectiveness of internal controls remains at an early stage. There is work outstanding for many companies ahead of the commencement of the new Provision 29, particularly in relation to reporting on non-financial controls. There were 25 companies in our sample that did not report at all, or did not report clearly, on whether a review of the effectiveness of internal controls had been carried out. On the other hand, although there were no early adopters of Provision 29 within the sample, a number of companies did refer to the new Provision and outlined the work ongoing to prepare for it, which was encouraging.

In our review of shareholder and stakeholder engagement, including workforce engagement reporting, we focused on whether companies report effectively on the outcomes of their engagement, as this is also a key area of focus in the new 2024 Code. We found some examples of good practice in this area, and we encourage companies to read the section of the review where these are set out.

This year, our review included reporting by audit committees on the Audit Committees and the External Audit: Minimum Standard, which is referenced in the new Code. We found some evidence of early adoption of the Minimum Standard which is encouraging.

We also considered how companies report on Audit Quality Reviews and found there has been an increase in the level of disclosure by audit committees of these inspection results.

While our 2024 Code consultation initially explored proposals in relation to 'over-boarding' – where directors' multiple board commitments potentially compromise their effectiveness – we ultimately decided against implementing new requirements to avoid increasing reporting burdens. Nevertheless, our review examined how companies currently address this issue in their annual reports. We were pleased to see good reporting in this area with companies generally setting out clearly the other commitments of their board members.

Overall, while reporting quality remains strong, there is still a need for more concise, outcomes-focused disclosure and enhanced reporting on risk management and internal controls. We encourage companies to read this review to inform their work. The FRC is also making available a series of podcasts, webinars and other materials to support the implementation of the 2024 Code, which can be accessed alongside this review.

Introduction

This review provides an overview of corporate governance reporting based on the annual reports of a sample of 100 randomly selected companies that follow the Code. However, given the focus this year on risk management and internal control, and as companies prepare for changes in the Code in this area, we have looked into this area in more depth and considered the annual reports of 130 companies. The sample of companies reviewed changes year-on-year and is a mixture of FTSE 100, FTSE 250 and Small Caps.

In July 2024, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) updated its UK Listing Rules, including the categories under which securities are listed on the Official List. As a result, there was a change in the companies required to follow the Code. Previously, the Code applied to premium-listed companies. Going forward, all those listed in the commercial companies category or the closed-ended investment funds category1 will need to follow the Code. All companies in the sample will continue to follow the Code after these changes.

The Code is flexible and enables reporting that is specific to each company. We do not expect a 'one-size-fits-all' approach, and in this review we have highlighted examples of good reporting that move away from boilerplate statements and provide meaningful information about governance activities and outcomes suited to their particular situation. Where we have included examples of good reporting in relation to specific areas of the Code, it is important to note that the FRC does not endorse these annual reports, as other aspects of reporting may require improvement.

The new 2024 Code, which becomes applicable from financial years starting on or after 1 January 2025, emphasises the importance of outcomes-based reporting. We were encouraged to see some strong examples of this already as part of this year's review.

A key feature of the Code's flexibility is its 'comply or explain' approach. This means companies can depart from a provision when circumstances warrant it, provided they offer a high-quality explanation of why their chosen approach constitutes good governance. This year has seen a decrease in the overall number of companies departing from the Code, which is explored in greater detail in the Code Compliance section of this review. It is encouraging that companies continue to use departures from the Code in other circumstances, However, as noted last year, there remains some room for improvement in the quality of explanations.

This review is the penultimate assessment of corporate governance reporting against the 2018 Code. We hope it proves informative for companies and other stakeholders, both in continuing to drive up the quality of corporate governance reporting in the UK and in helping companies prepare for the new 2024 Code.

Code Compliance

Compliance statement

It is important that users of an annual report are able to quickly understand how a company has applied the principles of the Code and the extent of compliance with the provisions. We found that most companies in our sample included a separate statement that confirmed they had applied the Code's principles and outlined whether they had complied with the provisions. A separate compliance statement can make it easier for the users of the annual report to understand the company's approach to following the Code and its use of the flexibilities offered.

In addition, many companies provided a table as part of their compliance statement or at the beginning of the governance report, often signposting to other pages of the report where an explanation of how they applied the principles could be found. However, in a few cases, such a table was ineffective in fulfilling its purpose. We found companies signposting to sections of the report rather than the actual page (for example, 'see our strategic report') or giving a short explanation that simply copied excerpts from the Code. We found the approach to reporting non-compliance and setting out explanations against the provisions to be inconsistent and unclear. Some companies that gave an explanation for non-compliance included it in their compliance statement. However, others directed readers to another part of the annual report without specifying exactly where the explanation was, for example, 'The explanation for non-compliance can be found in the governance section of the annual report'.

Key message

There is no single approach for how companies report their compliance with the Code in the annual report. However, good reporting helps a reader to understand how the company has applied the principles and determine whether it has complied with all the provisions of the Code. If the company has not, it also informs readers which provision the company has not complied with, and where to find the explanation for this.

Application of the principles

The Listing Rules require companies to explain how they have applied the principles of the Code in a manner that would enable shareholders to evaluate how the principles have been applied. Companies should apply each principle of the Code and report on how they have done so in the annual report.

The principles are high-level and not prescriptive, allowing companies to customise and apply them to their unique structures and circumstances. For instance, due to size, business model and geography, a UK FTSE 100 company may interpret the principles differently to an overseas-registered Small Cap company. the broad nature of the principles allows for a more nuanced and practical application.

In general, we found that while reporting on some principles is good quality, there are other areas where it could be improved.

Compliance with the Provisions

We have consistently emphasised that the provisions of the Code are not about rigid compliance. The FRC has steadfastly advocated against a one-size-fits-all approach, recognising that good governance can take various forms. Instead of demanding strict adherence, the Code is designed to provide companies with flexibility, aligning with their specific circumstances and allowing them to provide a valid explanation. This adaptability empowers companies to adopt bespoke governance arrangements.

Therefore, it is vital that, shareholders, service providers and other stakeholders support the flexibility of the provisions and do not anticipate complete compliance. When making investment and stewardship decisions, they are asked to assess the explanation provided by the company to determine whether it has implemented a governance approach that serves its interests, while also demonstrating good governance. While the Code sets out a framework there may be situations where good governance for a company requires a different approach than that outlined by the Code's provisions. In addition, sometimes non-compliance is unavoidable. It is, therefore, important to remember that the Code does not prescribe a rigid set of rules.

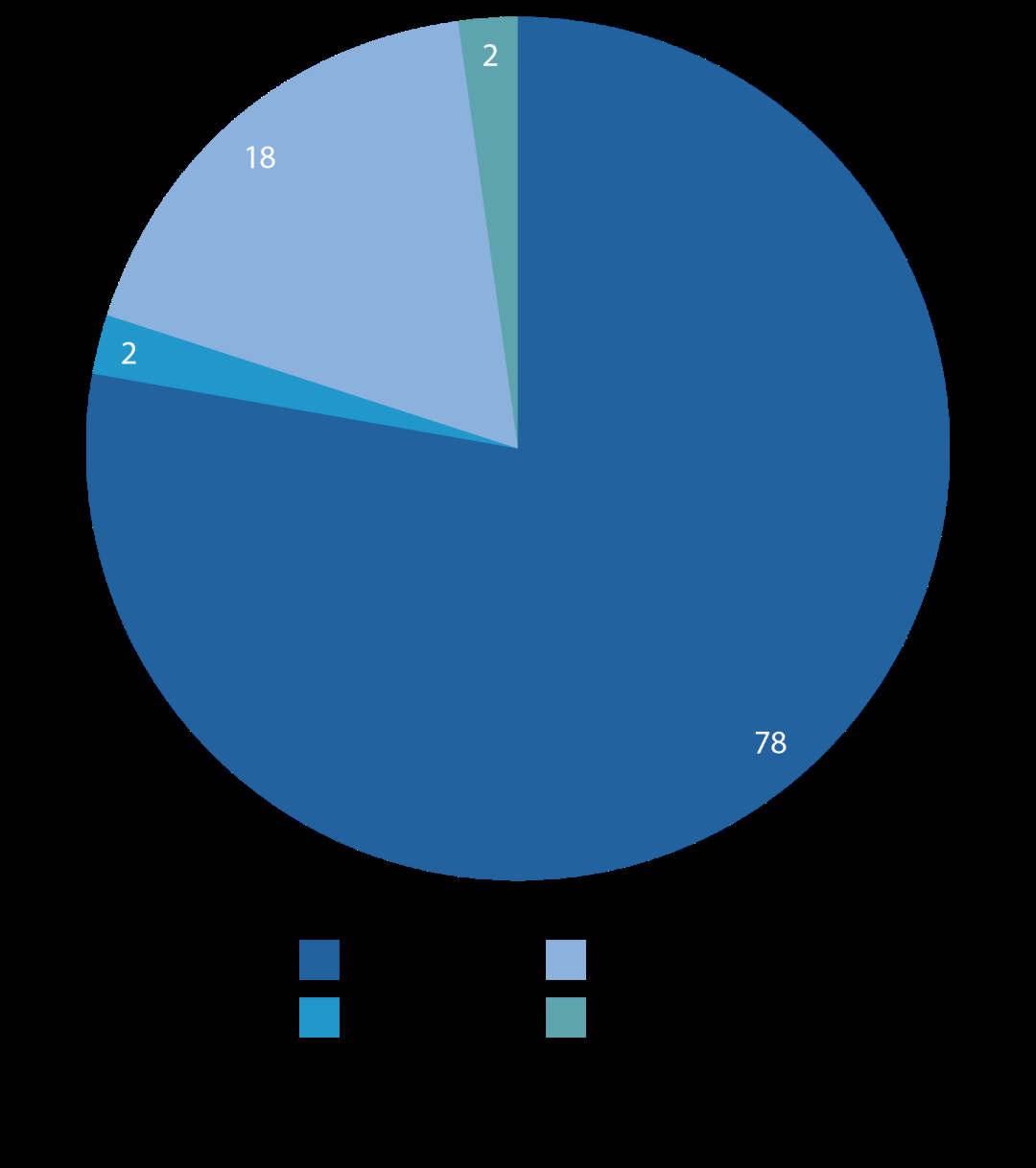

This year, fewer companies disclosed non-compliance with the Code's requirements. This can be primarily attributed to a growing number complying with Provision 38 (executive pensions aligned with those of the workforce). There was also a noticeable increase in compliance with Provision 19 (chair tenure), and a decline in non-compliance with other provisions, such as Provisions 9 (chair independence), 11 (board composition), 24 (audit committee composition), 32 (remuneration committee composition), and 41 (description of the work of the remuneration committee).

It appears this year that more companies have fully complied with the requirements of Provisions 24 and 32 regarding the membership of the audit and remuneration committees. Non-compliance with these provisions is generally temporary, often due to the sudden departures of directors from the board, The company is then brought to full compliance once new directors have been appointed. Non-compliance with these provisions is usually unavoidable rather than a choice. In these scenarios, an explanation would generally set out the reason for non-compliance and the time frame for returning to full compliance once a new director has been appointed.

| Annual review | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of companies | 64 | 73 | 63 | 28 |

Again, this year we found a small number of companies that did not disclose non-compliance with a provision in the annual report. This includes Provision 19 (chair tenure) and Provision 38 (pension alignment). The number of companies failing to disclose non-compliance is much lower than the previous one. Nevertheless, transparent reporting is important, and disclosure of non-compliance is a requirement of the Listing Rules.

Provisions with the highest non-compliance

Explanations

In our previous annual reviews, we have defined what makes a good explanation for non-compliance. Despite this, as in other years, we observed instances where companies:

- Did not explain non-compliance.

- Provided an explanation for one of the provisions they did not comply with, but no explanation for non-compliance with others.

- Acknowledged non-compliance and said that it had been rectified or would be rectified but did not explain the reasons behind it.

Explanations that were provided were often vague and lacked a clear rationale for why the company did not comply with the provision. In some instances, it was difficult to determine how the departure from the provision was in the company's interests.

We are told that companies have concerns about explaining against a provision, as this will lead to voting against resolutions at the AGM. Providing a clear and meaningful explanation is important as it influences shareholders' decisions and enables them, along with other stakeholders, to make informed choices about the company's approach to complying with the Code. We hope that dialogue with key stakeholders would mitigate votes against where good governance is upheld following an explanation.

A brief explanation can sometimes be understandable, particularly when non-compliance with a provision is unavoidable. For example, a sudden departure of a board member may lead to a short period where the number of independent non-executive directors (NEDs) is below what is expected. In these circumstances, it is important to provide information on the actions the company has taken to return to full compliance, including how effective challenge is encouraged at the board in the intervening period.

However, in other situations, more detail may be necessary. For example, some companies explained that the reason for the chair staying in their position beyond nine years (Provision 19) was their valuable experience or knowledge.

It may be difficult for investors and other stakeholders to accept non-compliance with such a simplistic explanation. You would expect a board member to have experience and knowledge, so why is the extension necessary? Without context, it is almost impossible to support such an explanation. Above all, it may be difficult to understand why the company has selected non-compliance with the Code, and it may fail to persuade the readers of the annual report that this is necessary or beneficial for the company.

In this instance, a good explanation demonstrates how the company benefits from the chair over another person, how the board has assessed any risks and any mitigation actions if needed.

We know that proxy agencies and some investors have policies that follow compliance with the Code. A good explanation will aid their understanding of why a provision is not being followed either for a short time or a longer period.

- 11 companies complied with the Provision during the year

- 3 companies said that they will comply with the Provision in a specified timeline

- 3 companies said that they will comply with the Provision in the future but did not provide a specific timeline

- 9 companies did not provide any indication as to whether the company plans to comply with the Code in the near future

Period of non-compliance

The Listing Rules require companies to explain 'the period within which, if any, it did not comply with some or all of those provisions'. If the company has not complied with the provision during the year, good reporting specifies the period in which the company was not compliant. If the company is planning to comply with the provision in the near future, it is valuable to give some indication as to when and under what conditions or circumstances. When non-compliance is indefinite, good reporters state this when explaining the reasons.

1. Board leadership and company purpose

Corporate culture

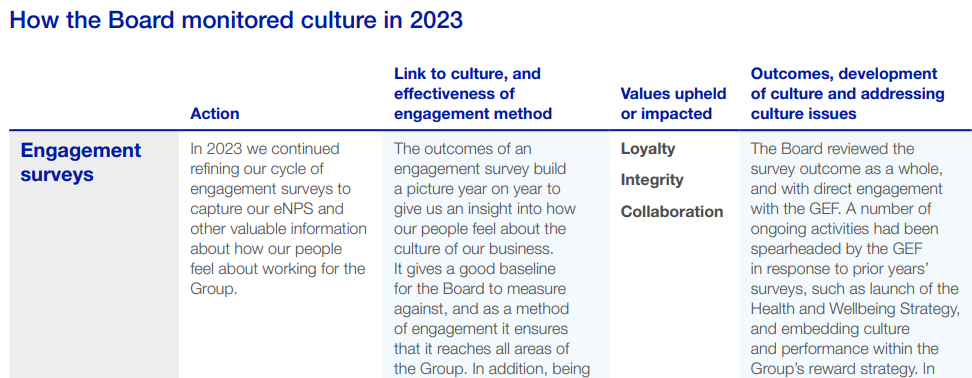

Disclosure of corporate culture continues to evolve. While the breadth of reporting has widened, the depth is lagging and in some cases, for example, culture assessment and monitoring, has decreased.

Overall, it is encouraging to see more organisations recognising the value that a positive culture brings to the business. One stated that culture lies at the heart of robust and effective governance while others expressed the view that culture drives organisational success and impact. A few companies attempted to demonstrate the positive outcome of their culture quantitively, for example see Weir Group below.

Source: Weir Group, p. 82

More companies are also extending their culture reporting beyond workforce to other stakeholder groups, such as customers and suppliers. Those two developments could be a result of greater interest expressed by investors and regulators in corporate culture, purpose and values, and how they are demonstrated by company leadership and linked to business model and strategy, as reported by some organisations. However, it is recommended that companies avoid turning the word 'culture' into a label or marketing tool, as observed in some annual reports this year. Overuse could negatively impact its meaning and importance.

Companies are being noticeably more transparent when the need for a greater focus on culture has been identified, for example during a board performance review, and when certain actions have been taken but outcomes are not yet known, which is commendable. However, clear signposting between the strategic report, where most culture reporting is usually placed, and the governance report is still a challenge for many organisations.

This may be one of the contributing factors behind the very limited disclosure in governance reports around how boards are promoting the desired culture (Principle B). Better reporters talked about it explicitly. They said, for example, how their boards were involved in reverse mentoring, directly engaged with the workforce and kept culture, purpose, values and strategy under regular review to ensure their alignment.

Promotion of desired culture by the board, as disclosed in the governance report

- 46 companies made no direct reference to culture promotion

- 22 companies made a reference but not in a board context

- 28 companies referenced the board but provided no narrative

- 4 companies supplemented their disclosure with a narrative

A few companies included a statement in their governance report saying that following their external board performance review, the evaluator concluded that the board has been effective in promoting the desired culture. Unfortunately, such statements lacked any evidence for the basis of this finding. We would encourage more transparency and rigour in reporting.

Key message

Disclosure in governance reports around how boards are promoting the desired culture is generally very low. More thorough reporting in this area and better signposting in the strategic report, where most of culture reporting is usually placed, is urged.

Corporate purpose and values

Year on year we have observed a slight increase in disclosure of corporate purpose, from 89 companies to

- However, only 33 organisations reported insightfully in this area this year, compared with 48 last year. Unlike last year, the number that explained their purpose in one sentence, often repeated in several places across the annual report, is greater than those that provided insightful explanations.

Better reporters explained each element of their corporate purpose and provided supporting narrative, at times even demonstrating direct links to the strategy and Key Performance Indicators.

Reporting of corporate values is steadily increasing from 73 companies three years ago to 76 last year and 79 this year. Meanwhile, the number of organisations referring to corporate values without disclosing what they are remains unchanged this year, after improving last year. Better practice in values disclosure is demonstrated by not only listing the values but also ensuring they are company-specific, explained and supported by a disclosure of matching behaviours.

Thoughtful reporting was demonstrated by those businesses that not only described in detail how they conducted the review of their corporate values but explained how the values were subsequently embedded (see next section). A bespoke approach to disclosure which is encouraged by the Code, was shown by some boards that reported on their activities in the year alongside values they demonstrated.

Assessment, monitoring and embedding

Disclosure around the alignment of corporate culture, purpose, values and strategy (Principle B) continues to fall, from 60 organisations three years ago to 40 this year. Among those that did explicitly discuss it, only a quarter did so insightfully, compared with around half last year and a quarter three years ago. On a more positive note, the number of reports without any references to the alignment between corporate culture, purpose, values and strategy has fallen year on year, from 23 companies to just nine.

Current wording in Provision 2 leaves room for interpretation as to whether organisational culture, purpose, values and strategy should all be aligned or just individual elements. The revised 2024 Code clarifies it is the former. Some businesses already report in this manner by providing a narrative, while others chose visual tools.

Source: Rathbones Group, p.19

Despite more organisations than ever reporting on culture assessment and monitoring, every year only a small number stand out in terms of high-quality disclosures. At the same time, 42 businesses disclosed a fair amount of detail for the last two years, which is an increase from 35 three years ago. However, compared with last year, we have observed more disclosure of policies and practices, rather than actions during the year. Better reporters evaluated effectiveness of each monitoring method and disclosed outcomes from their actions, see the example of Henry Boot Plc, a FTSE Small Cap company on the next page.

Source: Henry Boot, p.92

approach to culture assessment and monitoring, which might stem from greater understanding of what constitutes a desired culture for their companies.

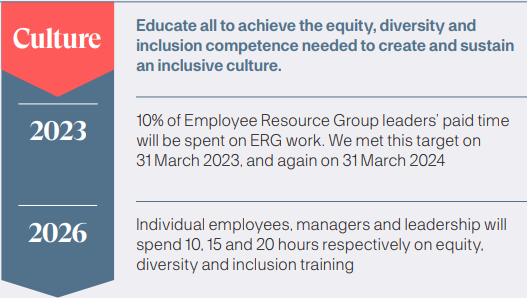

Explicit references to culture embedding – not in relation to risk management – have increased from 37 companies three years ago to 53 last year and 61 this year. However, most disclosures are limited, with 19 organisations including a simple narrative and 24 only referring to culture embedding among other things. Those that reported in this area insightfully explained the embedding process in detail, including different methods, action points, timeline and outcomes.

The 2024 Code asks boards to report, on a comply or explain basis, how they are assessing and monitoring the embedding of desired culture (revised Provision 2). We found some companies that have already acknowledged the new reporting requirement with a few even positioning their board's direct engagement with the workforce as their monitoring mechanism. Currently, culture embedding appears to be primarily described in the context of health and safety and ethics and compliance, with a few reporting on it through the lens of corporate values and behaviours.

Key message

While reporting on culture assessment and monitoring keeps increasing, this year more companies opted for disclosure of policies and practices, rather than board's actions during the year. We would encourage more transparency and rigour in reporting.

Metrics, targets and progress

In line with last year, over 20 companies disclosed a clear set of culture metrics and targets. In addition, we found that more companies this year also reported on progress against those targets.

Source: Tate & Lyle, p. 48

Most metrics used for culture reporting are related to health and safety (for example, work-related accidents or workforce engagement), Net Promoter Score and diversity and inclusion (mostly gender-related). Targets linked to customers and suppliers are rare. However, we noticed a slight increase in disclosure of metrics, some of which are then used by boards to assess and monitor organisational culture, for example the promptness of payments to suppliers. We also observed more disclosure around the use of culture dashboards, with some companies helpfully explaining the makeup of metrics.

A couple of organisations started using technological innovations including artificial intelligence (AI), to enhance board's strategic decisions by highlighting intersectional trends from received feedback. This is encouraging to see.

The FRC's 2021 report Creating Positive Culture – Opportunities and Challenges identified better use of data and insights as one of the key enablers in a high-quality culture assessment and monitoring.

Despite the Code not requiring culture assurance, 28 businesses reported on it. When culture assurance is undertaken, it is mostly done by the internal audit function or conducted externally. Only a few companies engaged their external auditor.

When conducting culture assurance, internal auditors tend to assess standards, training and conduct around compliance and ethics, risk and internal controls health and safety, speak-up arrangements and whistleblowing reports. Their findings often feed into the board's assessment and monitoring of culture. A small number of companies also reported on how their internal audit function assesses the extent to which behaviours reflect company purpose, ambition, values and strategy.

Source: Virgin Money, p. 96

Insights are also provided from the Culture Assessments conducted by Internal Audit which provide an independent analysis of the culture in specific business areas supplementing other culture measurement tools. Culture Assessments use a combination of surveys, leadership and broader colleague focus groups and selective in-depth interviews to measure the alignment between Virgin Money's intended culture and the culture that colleagues experience on the ground. Actionable insights and areas of good practice are identified. During the year the Culture Assessment approach was refreshed and a review was undertaken in the Business Operations area with the outcomes reported to the Audit Committee.

Shareholder engagement

Principle D

In order for the company to meet its responsibilities to shareholders and stakeholders, the board should ensure effective engagement with, and encourage participation from, these parties.

We are pleased to see that all companies reported on engaging with their shareholders during the reporting year, with 97 reporting on engagement that occurred outside of the AGM. However, like previous years we found little improvement in the quality of reporting on shareholder engagement. Most companies offered few details on the engagement, feedback received from shareholders or examples of outcomes.

Most companies provided details of the events they hosted for their shareholders during the reporting year. For example, one said they hosted 'regular market updates, investor presentations, 1x1 and group meetings, site visits and shareholder consultations'. As we have noted before such events offer some insight into the type of information that companies give their shareholders and illustrate their engagement plans during the reporting year.

However, good reporters went a step further and discussed how the information was received by shareholders and the issues raised. The best reporters explained the: * Frequency of the engagement. * Methods of engagement. * Topic engaged on, and whether this was a priority for their shareholders. * Feedback from investors. * Outcome of the engagement and whether it has made a difference in the decision-making process.

Source: Mondi Group, p. 95

Alongside this, Philip Yea (chair) held meetings with a number of Mondi's major shareholders during the year. There was no specific agenda for these meetings, but instead they were designed to offer open discussion and engagement. Topics covered included capital allocation, the disposal of Mondi's Russian assets, Mondi's approach to governance and culture, diversity and progress against Mondi's MAP2030 targets. In 2023, our Board also continued to engage with a cross-section of shareholders on developments and external expectations relating to executive pay. As a consequence, further meetings with investors were held to discuss particular features of the Directors' Remuneration Policy. Constructive feedback from investors is taken into account in determining the structure and operation of our remuneration policy.

This type of engagement in the example above shows how the company considered the views of its shareholders when developing its remuneration policy.

Reporting in more detail on activities and outcomes of the engagement with shareholders offers more insight to report readers.

Source: Costain Group, p. 67

Costain Group noted that during the reporting year, they consulted with their shareholders to discuss their remuneration policy renewal. As a result of "listening to feedback from the remuneration policy consultation, the remuneration committee made appropriate adjustments and (their) new policy received a vote in favour of 97%.”

The FRC plans to consult on changes to the Stewardship Code, which will cover a number of areas including greater emphasis on the importance of high-quality reporting on investor engagements.

Provision 3

In addition to formal general meetings, the chair should seek regular engagement with major shareholders in order to understand their views on governance and performance against the strategy. Committee chairs should seek engagement with shareholders on significant matters related to their areas of responsibility. The chair should ensure that the board as a whole has a clear understanding of the views of shareholders.

As described in Provision 3, engagement with major shareholders is an important element of good governance. We recognise that most 'business as usual engagement' is undertaken by investor relations teams, but it is essential that both the chair and committee members hear for themselves the issues that are important to their key investors. Such engagement can support future resolution and offer insight following a significant vote against a resolution.

| Number of engagements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Annual review | 2023 | 2024 |

| Chair | 52 | 68 |

| Remuneration committee chair | 63 | 75 |

| Senior independent chair | 13 | 20 |

| Nomination committee chair | 4 | 7 |

| Audit committee chair | 5 | 6 |

However, much of the reporting on engagement by committee chairs did not include specific outcomes. While outcomes can take time to materialise, it is important to include these where possible. It is good to see the number of engagements with board members and committee chairs has improved compared with last year's review.

Eighty-five companies in our sample noted that their investor relations function remained the first point of contact for shareholders. We encourage committee chairs to engage directly with their significant shareholders particularly in the event of a 20% vote against. Companies are reminded that a 20% vote against can provide an opportunity to help companies better understand reasons for voting against a resolution, and the extent to which pre-applied voting policies may have had any influence.

Key message

Explaining the outcome of engagement activities with shareholders adds meaning and purpose to reporting, although it is understood that outcomes can take time to materialise.

Stakeholder and workforce engagement

Principle D

In order for the company to meet its responsibilities to shareholders and stakeholders, the board should ensure effective engagement with, and encourage participation from, these parties.

Provision 5

The board should understand the views of the company’s other key stakeholders and describe in the annual report how their interests and the matters set out in section 172 of the Companies Act 2006 have been considered in board discussions and decision-making.

A significant number of companies in our sample identified governments and regulators as key stakeholders (see below).

Reporting on stakeholder engagement is of generally high quality and we continue to see more valuable reporting year on year

Engagement

This year, companies identified other types of stakeholders in addition to those specifically mentioned in section 172 of the Companies Act. Although not currently referenced in the Companies Act, it is important that organisations identify the stakeholders most important to their operations and explain how they engage with them.

While reporting on engagement is generally high quality, it is sometimes unclear how the board specifically (rather than management or other employees) engages with different stakeholders. However, we did see some good examples this year. One company (see below) was transparent in its explanation of how the board engages with customers.

Source: OSB Group, p. 120

The Board’s engagement with customers is indirect and Directors are kept informed of customer-related matters through regular reports, feedback and research.

We were pleased to see that one company explained how it measured the effectiveness of its engagement with each stakeholder group. Companies are encouraged to report on the effectiveness of their engagement with stakeholders to ensure they continue to be effective as their company evolves.

Source: Persimmon, p. 55

How do we measure the effectiveness of our engagement?

The following metrics are regularly reviewed by the Board when considering progress against our five key priorities: * HBF eight-week and nine-month customer satisfaction survey scores. * Trustpilot scores. * Speed of resolution of any customer issues. * Number of visitors to sites and levels of website traffic. * Volume of sales. * FibreNest's achievement of timely connections.

Outcomes

Reporting on outcomes could include how the feedback obtained during engagement was considered in board discussions and decision-making (which is also in line with the requirements of Provision 5 of the Code), as well as any actions taken by the board.

Key message

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the engagement, it is important to explain the engagement undertaken during the year and any outcomes.

Reporting on outcomes also aligns with the new Principle C in the revised 2024 Corporate Governance Code, which states that 'governance reporting should focus on board decisions and their outcomes in the context of the company's strategy and objectives.'

The 2024 Code places greater emphasis on the importance of outcome-based reporting which we hope will reduce boilerplate reporting and the length of annual reports. We have previously discussed the importance of companies reporting on outcomes of stakeholder engagement to demonstrate the impact of governance practices. We hope that introducing this principle will help companies make greater progress in this area. It is important to emphasise that we do not expect an outcome to arise or to be included in the annual report, for every engagement with stakeholders. We encourage companies to use outcomes-based reporting where it demonstrates an effective engagement mechanism that they wish users of the annual report to be aware of.

Many companies provided a section that lists issues of importance for each stakeholder group. However, without explaining the engagement undertaken and the feedback received, these issues seem to be arbitrarily chosen by the company rather than determined through meaningful dialogue between the board and stakeholders. In addition, many companies did not give further detail about the action that the board or the company will take to address them.

Source: Indivior, p.30

Suppliers and distributors

Indivior has a small supply chain which is critical to effectively conduct its day-to-day business.

Key stakeholder issues

- Product quality requirements and terms of business.

- Contractual terms and payment timings.

- Product pipeline and development plans.

- Tender process details.

- Climate change information.

Key issues for Indivior

- Product quality is essential for regulatory and compliance purposes and to ensure patient safety.

- A reliable supply chain is critical to the effective and regular distribution of treatments.

- It will be necessary to work closely with suppliers to collect Indivior's Scope 3 emissions data.

It was interesting to see that Indivior noted the key issues for stakeholders from the perspective of both the company and the stakeholder groups.

Many companies reported on the outcomes of the engagement, particularly engagement with their workforce. This covered how the feedback received was considered in board discussions or decision-making, and/or any actions that were taken as a result.

It is important to note that engagement does not always require the board to take action.

However, when action is taken, it is considered good governance practice to explain it in the annual report. Companies do not need to provide excessive detail, but they could demonstrate in a concise way, that the board is considering the views of the workforce and addressing any areas of concern or improvement, as seen in the Spirax-Sarco example.

Source: Spirax-Sarco Engineering, p.131

Management actions arising from our colleague engagement

We share and discuss the general themes from each meeting with local and divisional management and we ask them to share with the Committee any actions that arise from the feedback. This has proved to be very effective and we set out just a few examples of action taken:

Discussion Group Feedback: Management Action: A sales team requested greater autonomy to support customers with faults or replacement parts and questioned layers of approval required. Local managers met with Divisional Sales Managers to understand their concerns. As part of the Group Finance G3 governance project, the Delegation of Authority (DoA) was updated to empower within the context of G3 and to ensure clarity for managers on the approval process. Challenges in understanding and implementing the business strategy in day-to-day roles. We heard the message: "show me the strategy, don't tell me; I want to understand my role in these strategies." One of our Businesses created 'stand up' meetings in supply sites; these were shorter learning sessions on topics such as the strategy goals and implementation. 'Purpose workshops' were developed for managers to focus on personal contribution to Company strategy. Colleagues requested greater clarity on pay structure/progression and rewards. The Company took a series of steps, including setting up a working group, making use of an app for colleagues to communicate directly with the payroll team and introducing HR surgeries/ clinics for colleagues to drop in with queries and concerns. Remote roles such as Sales and Service Engineers are working more independently than before, and there is limited downtime and no opportunity to speak whilst driving etc. The Group refreshed and reinvigorated its focus on National Sales Manager monthly 'check ins' with all field-based Sales Teams as well as a quarterly collaboration event among Service the teams.

Some companies included a segment in the stakeholder section of the annual report under the heading 'outcomes'. However, it was unclear whether and how the outcomes were related to the engagement undertaken during the year. Good reporters demonstrated a clear link between engagement activities with their stakeholders and the outcomes reported.

The new Code guidance suggests ways in which companies might demonstrate how stakeholder engagement impacted board decision making. Following the stakeholder engagement feedback cycle, companies are encouraged to report on the inputs, outputs and outcomes of their engagement.

Workforce

Effective engagement, for purposes of Principle D, includes two-way workforce engagement. Employees are important stakeholders. Direct meetings, where the board actively seeks people's views and responds to their feedback, benefit both parties. Board members can gain valuable understanding by actively engaging with employees and taking their feedback into account. They can get a direct overview of their experiences and interests, the company's culture and how the company's values have been embedded throughout the business.

It also presents a great opportunity for the board to develop a deeper understanding of the company's operations, business model, and strategy, including risks and opportunities, as well as environmental and social matters. For instance, conducting site visits can give the board an overview of workforce conditions, management efficiency and the impact of business on the wider community. We were pleased to find that two-way engagement, such as meetings between board members and the workforce or board site visits, is a common practice.

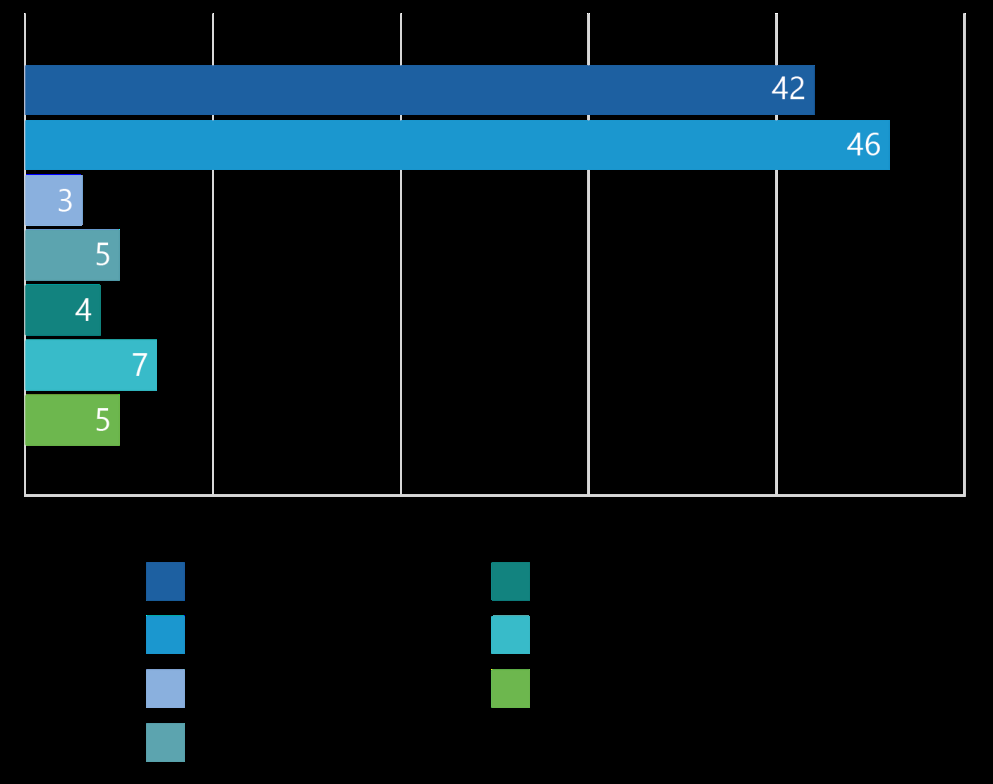

Eighty-five companies reported engaging in this way during the year. It was conducted either via one of the mechanisms set out under Provision 5, an alternative method or through both.

Methods of engagement

Provision 5 states that the board should select one of the Code's prescribed methods for engagement, or it could choose another way to engage with the workforce and explain why this is effective. Companies are not required to disclose their engagement method, however, most did.

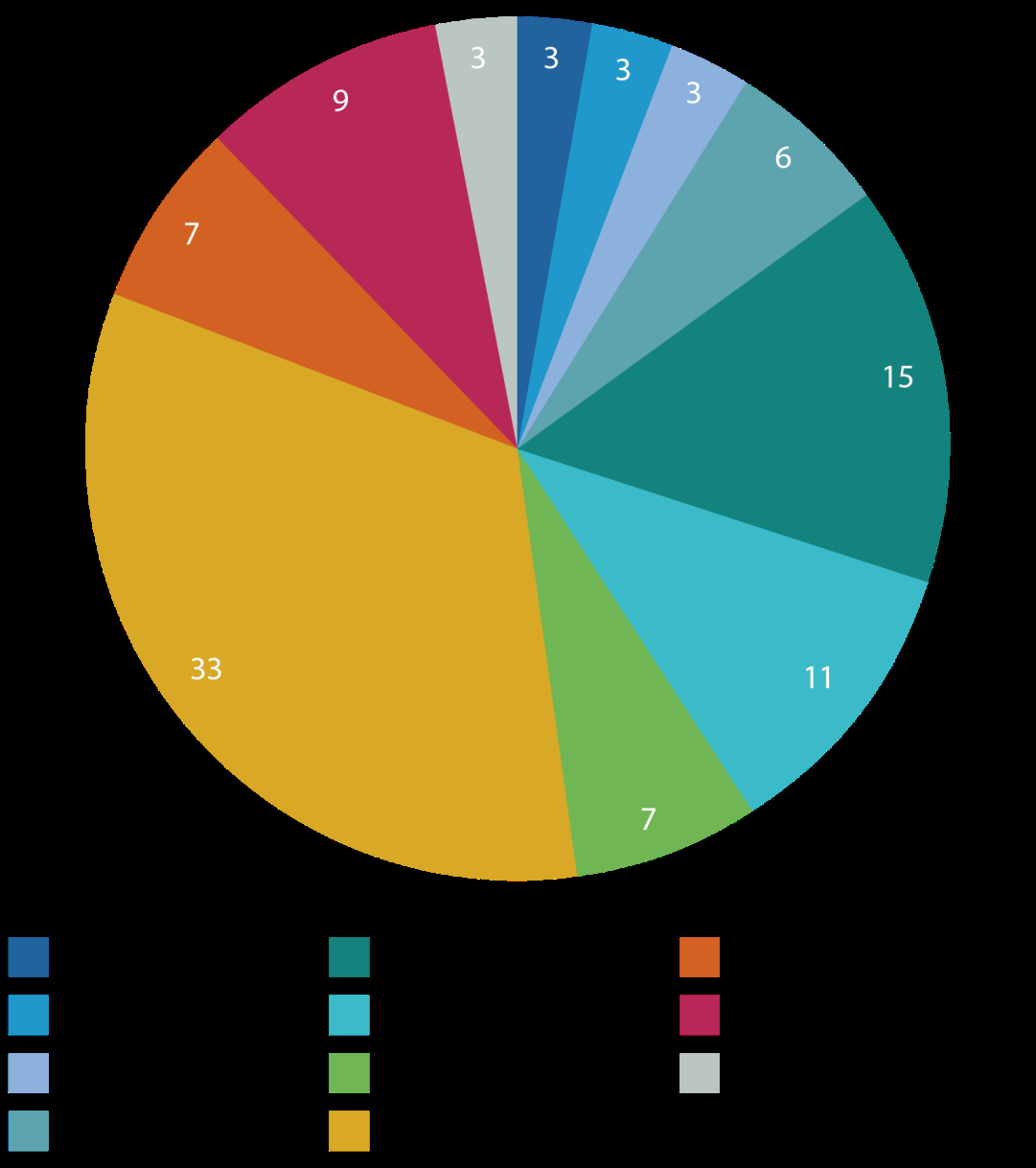

- 55 companies engaged using a designated NED

- 8 companies engaged using a Workforce Advisory Panel

- 9 companies engaged using both designated NED and Workforce Advisory Panel

- 20 companies engaged using alternative method(s)

- 8 companies did not state or it is unclear if they adopted one of the mechanisms prescribed by the Code (this does not mean that they have not complied with the Code as it is not a requirement to disclose this specific information)

As in previous years, a designated NED was the most popular method of engaging with the workforce. This can be a practical approach, with a NED having a clear and focused role as a link between the board and the workforce, and sharing employee insights with the board.

Most companies indicated in their report that the designated NED had directly engaged with the workforce during the year to gather their perspectives on various matters. However, some companies did not disclose whether their designated NED had engaged directly or conducted other activities to understand the workforce's viewpoint. If such engagement has occurred during the reporting period, companies could consider disclosing it in the annual report. This not only illustrates compliance with the Code, it aligns with good governance practice.

Seventeen companies reported having established workforce advisory panels, with eight of these also having a designated NED for workforce engagement. A panel can be a useful mechanism as it brings together various workforce perspectives, particularly when the company operates across different markets and geographies.

Most companies explained how the panel communicated the workforce's views to the board. Good reporting outlined the frequency of the panel's meetings during the year and how their views were conveyed to the board. Companies with both a workforce panel and a designated NED explained that the NED regularly attended the panel's meetings, while other companies reported attendance at the meetings by other NEDs, including the board chair and committee chairs. Two companies reported that panel members had been invited to attend board meetings.

As in previous years, we did not have a company in our sample with a director elected from its workforce. This can add value to the boardroom by incorporating workforce's experience directly into board discussions and decision-making. It may also be easier for employees to share information and honest opinions with someone nominated directly by them. Through our engagements, we have found that some investors support workforce-nominated directors on boards.

Alternative arrangements

Provision 5 states that if the board has not chosen one or more of these methods, it should explain what alternative arrangements are in place and why it considers them effective. This ensures a company can still fully comply with Provision 5 even if it has not selected one of the methods set out by this provision.

It is important that engagement mechanisms are tailored to the company's circumstances including its structure and strategy. Twenty companies had chosen an alternative arrangement than those set out in the Code to engage with the workforce. Fifteen of them explained that due to their geographical reach, it would be difficult to have a single designated NED to cover the engagement. Therefore, it was more practical for the company to have several or all of the board members engaged with the workforce in different locations. In addition, three other companies had established board committees responsible for workforce engagement.

Only two companies did not explain how their alternative engagement methods were effective, so did not comply with Provision 5.

Source: Spirax-Sarco Engineering, p.131

Benchmarking – Each year, the Committee undertakes an evaluation of its effectiveness and at least one benchmarking activity to ensure our activities reflect best practices and are in line with the regulatory requirements. Additionally, we use this as an opportunity to review what other opportunities for colleague engagement might be feasible and effective for our Group. This year, the Committee reviewed the colleague engagement approaches implemented by a selection of peer businesses within the FTSE 100 and considered whether some of those approaches might be beneficial for our own Committee agenda. In general, the Committee believes that it is working well and that it is adding value to the Board and this is supported by feedback from the Board, the executive and the wider organisation. Committee members are keen to interact with even more colleagues when undertaking site visits in 2024.

Provision 5 of the Code states that companies should keep their mechanisms under review so they remain effective. The above example is also a good illustration of how a company can evaluate its engagement mechanisms and describe its approach in the annual report.

Board engagement

One company reported that it had decided to carry out an employee survey as an alternative way of engagement, and another said it engaged through senior management reporting periodically to the board. Surveys may be a good opportunity to obtain more detailed and honest (if carried out anonymously) feedback from the workforce. In addition, engagement by senior management can be beneficial for both the workforce and the company.

However, to meet the requirements of Principle D and Provision 5, and as a matter of good practice, the board should carry out its own engagement with the workforce in addition to any engagement undertaken by senior management. The board can delegate this responsibility to one or more NEDs or a board-level committee, but it cannot delegate it to senior management or rely solely on surveys carried out by the management or external parties.

Reporting on workforce engagement in the Annual Report

To demonstrate how their engagement has been effective (as per Principle D), good reporters provided an overview of the engagement undertaken during the year, the themes discussed or feedback received, and the actions taken by the board to address that feedback.

Many companies provided a good overview of their activities, for example, meetings with the designated NED and site visits by different NEDs.

Source: Associated British Foods, p.84

Since my last report I have spent face-to-face time with our people in their offices, factories, stores, and out in the field. In these discussions I have been able to understand how they view our Group and their specific business and location. I have spoken with: * operations, commercial and management teams from Twinings Ovaltine in Andover and New Jersey; * employees from the Argo factory and the Chicago Head Office in ACH; * retail assistants, store supervisors, managers, and regional HR * business partners at Primark's Chicago store and at two different Primark stores in New Jersey; * employees across a range of teams and departments at SPI Pharma in Grand Haven, Michigan; * participants of the Thrive development programme at George Weston Foods businesses in Australia; * employees from operations and product merchandising from Tip Top in New South Wales, Australia; * a wide variety of employees from our Don business in regional Victoria, Australia; and * the team in our Yumi's business based in Port Melbourne, Australia.

My visits also enable me to connect with our people through unions or other local collective arrangements, for example with the union representative for our Don business. I am also grateful for the input from fellow Board members who have visited our businesses including Acetum, Illovo and Primark during the year.

Only 30 companies reported on the outcomes of the engagement. Good reporters provided a summary of how feedback received impacted board discussions and decision-making and any actions taken as a result.

Communities

Section

- (d) of the Companies Act 2006 stipulates that companies should have regard for the impact of the company's operations on the community and the environment.

We have previously observed that reporting on the impacts of companies' operations on local communities is boilerplate and provides very little valuable information for the users of reports. Only 63% of companies identified the community as a stakeholder, independent of the environment.

The majority of companies only shared positive community and charitable initiatives without explaining the impact of their operations. Some companies used phrases like, 'we wish to minimise the negative environmental and social impact that we may have' without explaining what those impacts may be and any action they are taking to achieve this objective.

Board discussions and decision-making

While engagement with some stakeholders, such as the workforce, may be straightforward for the board, it can be more difficult to engage directly with other stakeholder groups, for example consumers or communities. It is understandable that the board may not engage with these stakeholders to the same extent as it does with the workforce.

Nevertheless, the board, for the purposes of Provision 5, should be kept updated about these stakeholders' interests and viewpoints and consider them in their discussions and decision-making.

Section 172 of the Companies Act 2006 lists a number of stakeholders. However, the board can also engage with other stakeholders or consider them in their discussions or decision-making. For example, some companies reported engagement with their lenders, regulators or governments.

For the purposes of Provision 5, the board does not need to provide considerable detail on how these stakeholders and the matters under section 172 have been considered. Good reporting provides a concise summary demonstrating that the board considers these during meetings and when making decisions.

Many companies provide case studies or examples of decisions to show these considerations. However, it is often unclear whether these are simply decisions taken by the company as part of its strategy or actual decisions made by the board. Often, companies just use icons to point out which stakeholders had been considered but do not explain how.

In addition, under a 'Section 172' heading, some companies provided information on what the company does for groups of stakeholders, such as employee training or charity and environmental initiatives. However, they did not refer directly to the board discussions or decision-making.

Good reporting for the purposes of this provision demonstrates how the board has considered the company's stakeholders and other factors under section 172 in their discussions and decision-making.

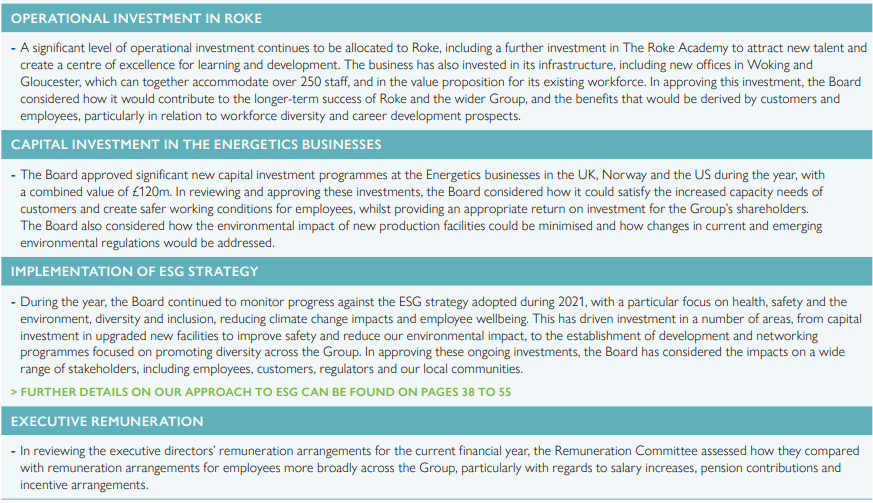

Source: Chemring, p.87

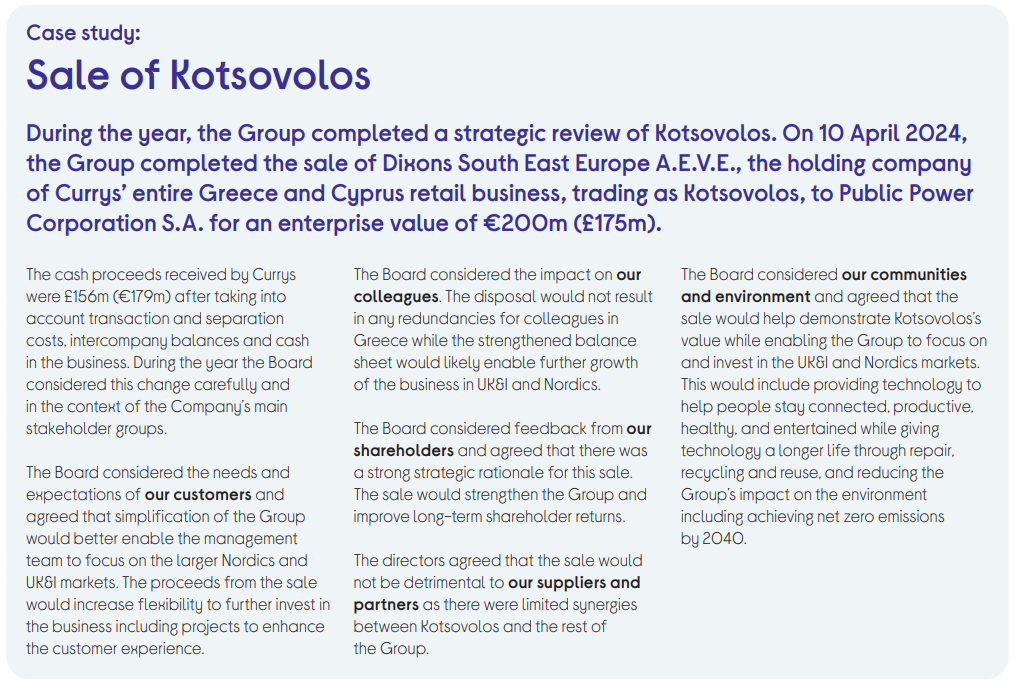

Source: Curry's, p.29

Case study: Sale of Kotsovolos

During the year, the Group completed a strategic review of Kotsovolos. On 10 April 2024, the Group completed the sale of Dixons South East Europe A.E.V.E., the holding company of Currys' entire Greece and Cyprus retail business, trading as Kotsovolos, to Public Power Corporation S.A. for an enterprise value of €200m (£175m).

Environment

In line with previous years, environmental matters, including climate change, continue to be a prominent subject in the annual reports. The Code does not have specific reporting requirements on environmental issues other than the requirement under Provision 5 asking companies to disclose how the board has considered Section 172 matters in its discussions and decision-making. The environment is one of the factors listed under Section 172 of the Companies Act, and most companies provided some indication of how it was considered in board discussions and decision-making.

Forty-eight companies reported having a designated board-level committee responsible for environmental matters (including climate change), many of which were created in the past two to three years.

These committees were often designed as ESG, CSR or sustainability committees and also had responsibilities for other matters such as stakeholder engagement, health and safety and company reputation.

While having such a committee is not a Code requirement, it is encouraging to see boards developing bespoke governance arrangements to oversee environmental matters.

Committee responsibilities differed between companies and included: * Reviewing environmental policies. * Monitoring environmental impact and performance, for example energy and carbon emissions, and waste management. * Reviewing environmental-related risks and opportunities. * Overseeing compliance with applicable government and industry Standards. * Overseeing environmental-related reporting, including Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) reporting.

For most companies, this designated committee was made up entirely of NEDs. Some companies reported that senior managers, such as the CEO, were part of this committee. In two companies, the committee included a mix of NEDs and senior managers (for example, the CEO, CFO, CRO and company secretary).

Companies that did not have a designated committee reported that the board as a whole had responsibility for environmental matters. Many said their audit committee had some delegated responsibilities, usually for environmental-related risks and reporting. One company reported that the audit committee was also responsible for overseeing the level of carbon emissions. We were pleased to see some companies reporting cross-work between different board committees on environmental matters, for example, the audit and sustainability, risk or remuneration committees.

In addition, 37 companies reported having a committee at the management level with responsibilities for environmental matters. Good reporters provided details on how such a committee worked with the board. However, for some companies, it was unclear how the work of the management-level committee was reported to the board or its committees.

While it is not a Code requirement, 35 companies provided a summary of the activities of the designated committee during the year. This may be helpful for users of the annual report to understand the board's role and its approach to dealing with environmental matters.

Source: Compass Group, p.91 During the year, the Committee reviewed with management the Group's sustainability strategy including the plans to reach climate net zero by

- The Committee reviewed the progress made during the year on reducing the Group's Scope 1 and 2 emissions. The Committee also considered the Group's key activities to reduce Scope 3 emissions which centred around food waste reduction, re-engineering menus and collaboration with suppliers. The Committee also received an update on progress on the UK&I business' commitment to reach climate net zero by 2030, and reviewed the roadmap in detail. More detail of Compass' progress on its sustainability strategy and net zero commitments can be found in the Purpose report on pages 38 to 44.

In September 2023, the Committee reviewed the Company's proposed TCFD disclosures to be included in the 2023 Annual Report and Accounts. In addition, the Committee received a training session led by the Sustainability team, external advisers and the Company's external auditor on the wider ESG landscape, including forthcoming sustainability disclosure requirements. Further information can be found on page

-

To better understand and mitigate the Group's food waste footprint, the use of food waste tracking technology has been expanded across the Group's operations to help towards Compass' commitment to halve food waste in its operations by 2030. Aligned to this commitment, the Group introduced a non-financial food waste performance measure related to the number of sites across the Group's businesses adopting the technology for the financial year ended

-

Achievement of the food waste performance measure is linked to 5% of the annual bonus of executive directors and senior management. The Committee is pleased to report that excellent progress has been made during the year with 7,943 sites globally now employing food waste tracking technology to record food waste.

Suppliers

The relationships companies have with their suppliers are crucial to long-term success. Ways in which companies maintain good relationships with their suppliers include working together on workforce issues such as modern slavery, agreeing approaches to environmental and climate change challenges and ensuring payment practices align with their policies and contractual obligations.

Targets linked to customers and suppliers are rare. However, we noticed a slight increase in disclosure of metrics, some of which are used by boards to assess and monitor organisational culture – for example, the promptness of payments to suppliers, as one company reported.

Source: Spirax-Sarco Engineering, p.119

The Board monitors and assesses culture using the following mechanisms: promptness of payments to suppliers, approach to regulators.

In our sample, 42% of companies referenced supplier payment terms. Eighteen companies explicitly defined their prompt payment policy, 16 companies noted that they are signatories to the Prompt Payment Code (PPC) and five said prompt payment is a priority for the board. This information gives an indication as to the importance a company gives to paying suppliers in a timely manner.

Barclays, for example, noted that it is a signatory to the PPC and its board is committed to the fair payment and treatment of its suppliers.

Source: Barclays, p.238

Prompt payment is critical to the cash flow of every business, and especially to smaller businesses within the supply chain as cash flow issues are a major contributor to business failure. We aim to pay our TPSPs within clearly defined terms, and to help ensure there is a proper process for dealing with any issues that may arise.

We measure prompt payment globally by calculating the percentage of TPSP spend paid within 45 days following invoice date.

The measurement applies against all invoices by value over a three-month rolling average period for all entities where invoices are managed centrally. At the end of 2023, we achieved 93% on-time payment to our TPSPs compared to 93% at the end of 2022, exceeding our public commitment to pay 85% of TPSPs on time (by invoice value). The need to promptly pay our diverse TPSPs became even more important during the COVID-19 pandemic. Barclays established a process to expedite the payments for diverse TPSPs at this critical time. This process remained in place during

- Barclays is proud to be a signatory of the Prompt Payment Code in the UK and we also work closely with the Small Business Commissioner and other organisations, including Good Business Pays, to educate the public on late payments and the impact they can have on businesses and business owners, and to raise the social conscience of larger businesses who do not pay on time.

2. Division of Responsibilities

Over-boarding

Principle H:

Non-executive directors should have sufficient time to meet their board responsibilities. They should provide constructive challenge, strategic guidance, offer specialist advice and hold management to account.

Directors must have sufficient time to carry out their roles and to fulfil their responsibilities under section 172 of the Companies Act 2006 to promote the long-term success of the company, generating value for shareholders and wider stakeholders. The Code does not specify a maximum number of board appointments that can be held by a NED as the time commitments for each role will vary depending on their responsibilities and whether for example, a director is part of a board committee or is the chair of a board. It is important that full-time executive directors do not take on more than one non-executive directorship in a FTSE 100 company or other significant appointment.

Nearly half of the companies in our sample stated that all directors have sufficient time to carry out their role effectively, while a further 15 only specified that their NED's have sufficient time to fulfil their duties. The majority of other companies explained that they review the commitments of directors to ensure they have sufficient time to fulfil their duties.

No executive directors in our sample had more than one non-executive role in a FTSE 100 company, in line with provision 15 of the Code.

Encouragingly, over 90% of companies in our sample provided specific information on the external commitments of directors and over 65% listed all directors' other appointments. The majority of companies simply listed directors' external appointments in the directors' biographies section of the annual report. However, some companies provided specific information on their considerations of individual directors' time commitments and explained the actions taken to manage their time commitments.

One company explained that as a result of concerns about the number of appointments of a director's other listed directorship, it contacted major shareholders who voted against the re-election of the director to understand their views. The company explained that the director's attendance record was exemplary and that they participated in a number of additional opportunities throughout the year.

Key message

Companies are encouraged to be transparent in their annual report and disclose information about the time commitments of their directors.

Good reporting will include factors that the board took into consideration when reviewing the time commitments of a director.

A small number of companies in our sample said they note the views of a variety of investor bodies and institutional investors to foresee any perception of over-boarding.

Although some good reporting was identified, there is still a significant amount of boilerplate reporting. Many companies used phrases such as 'no instances of over-boarding were identified during the year' with no further discussion around the time commitment of their directors.

Several companies disclosed information about their consideration of approving a change to their external appointments.

Source: BAE Systems, p.90 In compliance with Provision 15 of the Code, the Nominations Committee considered [a director's] other commitments prior to his appointment to the Board as a non-executive director in

- In particular, it noted his other listed company board appointments, being his role as non-executive Chair of James Fisher & Sons and non-executive director positions at Ashtead Group and STS Global Income & Growth Trust. Prior to his appointment, it was confirmed that he would be stepping down from the STS Global Income & Growth Trust at its AGM this year. Recognising that [the director] will be stepping down from a listed company board later this year (most likely in July) and that all of his other corporate interests are non-executive in nature, the Board is satisfied that he has sufficient time to undertake his duties as a non-executive director of the Company.

Board committees

Disappointingly, companies in our sample did not disclose much information about the board committees their directors serve on in their external appointments. Fewer than 10% of companies listed whether their directors are part of a board committee in their external roles and a further 26% only disclosed this information if the director was a board committee chair. Serving on a board committee can be time consuming and can involve a wide range of responsibilities that can be intensive and call for additional involvement. Boards are advised to take this into consideration when reviewing the time commitments of their directors.

Over-boarding policy

We found that the majority of companies included some consideration of the time commitments of directors in their annual report. Most companies explained that directors' external commitments are considered on appointment and that additional appointments require prior approval of the board.

One company disclosed its over-boarding policy which stipulates how many external appointments a NED should have. However, the vast majority of companies were not as specific in their policies. Examples like the one below, demonstrate some factors that are considered by companies when assessing the time commitments of their directors. In compliance with Provision 15 of the Code, the Nominations Committee considered [a director's] other commitments prior to his appointment to the Board as a non-executive director in

- In particular, it noted his other listed company board appointments, being his role as non-executive Chair of James Fisher & Sons and non-executive director positions at Ashtead Group and STS Global Income & Growth Trust. Prior to his appointment, it was confirmed that he would be stepping down from the STS Global Income & Growth Trust at its AGM this year. Recognising that [the director] will be stepping down from a listed company board later this year (most likely in July) and that all of his other corporate interests are non-executive in nature, the Board is satisfied that he has sufficient time to undertake his duties as a non-executive director of the Company.

Source: Dr Martens, p.98 The Board considers the number of board positions that the Director holds at other public companies alongside the likely 'size' of their new role. It also takes into account externally published guidance and proxy voting guidelines to ensure the principles of major investors in respect of 'overboarding' are considered.

When calculating the expected time commitment, boards are advised to consider the additional commitment needed when the company is experiencing increased activity, for example during a period of distress, and the role that individual directors are likely to play on committees of the board, including possibly chairing these, form part of this consideration.

Board performance review

Fewer than 30% of companies disclosed that they considered directors time commitments to other organisations as part of their annual board performance review. Those that did provided very little information on what they considered to determine whether each director has sufficient time to fulfil their duties.

Reviewing the external appointments of directors as part of a company's annual board performance review can be an effective way of monitoring any change to the time commitments of directors.

Companies in our sample reviewed directors' external appointments through, for example: - A register of directors' commitments maintained by the company secretary that is reviewed at each board meeting. - Their nominations committee. - One-to-one discussions with the chair. - An annual review by the board of NEDs' external appointments.

Diversity

Provision 23

The annual report should describe the work of the nomination committee, including: [...] - the policy on diversity and inclusion, its objectives and linkage to company strategy, how it has been implemented and progress on achieving the objectives

Similar to previous years, the approach to reporting on diversity policies varied. Some companies cited that they had diversity policies but did not provide a description of what the policy entails. Others gave generic descriptions of what their diversity policy includes without referencing any specific targets or objectives for how they aim to improve their diversity.

However, it was encouraging to see 59 companies provide clear information about what their board diversity policy covers, their targets and objectives and the progress they have made to achieve these. Convatec Group noted its diversity targets and objectives and documented the current progress. They noted that they aim to achieve higher representation of women in senior management through a leadership development programme.

Source: Convatec Group, p.108 - As part of our ongoing diversity and inclusion strategy, our target is to achieve 40% of senior management roles to be held by women by 2025. - By 2023...women represented 44% of board members and 44% of their Senior Management team. This was previously 40% in 2022 for the board and 38% in 2022 for Senior Management.

It has been very encouraging to see a minority of companies provide forward-looking explanations to show how they will continue to monitor progress in the year ahead to meet their targets.

Source: Shell Plc, p.173 Women representation in the top 1,200 roles ("Senior Leadership" positions) has strengthened by 2% during 2023 to 32%, and we continue to progress towards our aim of achieving 35% women senior leadership representation by 2025.

Gender and ethnicity targets

A key component of our analysis was to investigate how gender and ethnicity targets were reported in annual reports. Many companies align their own targets with the FTSE Women Leaders Review and Parker Review targets. The FTSE Women Leaders Review target is to have 40% women representation on the board by the end of 2025 for FTSE 350 companies. Fifty-five FTSE 350 companies within our sample of 84 companies already meet this, which is an 18% increase from last year's sample. We anticipate a rise in the number of companies that will achieve these targets in the year ahead.

The 2024 Parker Review encourages FTSE 250 companies to have at least one ethnic minority director on the board. Out of 41 FTSE 250 companies, we found that 32 FTSE 250 companies have met this target.

This year we examined whether companies had stated whether they were working towards the 2027 Parker Review targets for FTSE 350 companies. The 2027 targets will require companies to set their own targets for the percentage of senior management who self-identify as being from an ethnic minority background. Twenty-two FTSE 350 companies and one Small Cap company referenced their aim to work towards these targets, demonstrating the importance of achieving greater diversity within their organisation.

We also assessed the extent to which the 2022 Financial Conduct Authority's Listing Rules (LR 9.8.6R(9) and LR 14.3.33R(1)) were reported on. The targets operate on a comply or explain basis. Like last year, one measure we explored was whether the companies in our sample had a woman appointed to at least one of the senior board positions (Chair, CEO, Senior Independent Director, or CFO). The table below shows the total number of women in the top four senior leadership roles in our sample of 100 companies.

| Chair | Senior independent director | CEO | CFO |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 49 | 6 | 13 |

Initiatives and objectives beyond Parker Review and the FTSE Women Leaders Review targets

Eighty companies reported on diversity initiatives targeted at senior management, boards and the workforce. The quality of information provided for these initiatives and objectives varied. However, most of these companies reported on employee resource groups for example the LGBTQ+ Network that advocate for the workforce.

Good reporting on initiatives described the contribution towards improving diversity at board level and senior management.

Source: HSBC, p.77 In our 2023 Accelerating into Leadership programme, which prepares high potential, mid-level colleagues for leadership roles, 43% of participants were women. More than 5,200 women also participated in our Coaching Circles programme, which matches senior leaders with a small group of colleagues to provide advice and support on the development of leadership skills and network building.

One company described an initiative designed to address the needs of the level of leadership below the executive committee and directors.

Source: Henry Boot, p.105 The Committee has oversight of the Company's Senior Leadership Development Programme (SLDP) through which we have given development opportunities to a significant number of senior management. Our Leadership Development Programme (LDP)... is a cohort-led development opportunity to address the needs of the next level of leadership below Executive Committee and Director level.

However, companies in our sample rarely reported on the outcomes of their initiatives or disclosed their impact on improving representation on boards or among senior leadership.

We have made changes to the 2024 UK Corporate Governance Code that included the removal of a list of diversity characteristics, to encourage companies to think about diversity more widely. We have also added a new reference to diversity initiatives to help companies to think beyond formal policies when it comes to diversity and inclusion.

It was encouraging to see some companies report on targets and initiatives for diversity characteristics beyond gender and ethnicity. For example, Lloyds Banking Group noted, it has a target to double the number of disabled colleagues in senior management by 2025.

Overall, it has been positive to see the progress companies have made in reporting on objectives and targets, and on developing diverse boards and senior management teams. We hope to see organisations continue to report on their progress and set out the outcomes of their diversity initiatives.

Key message

Many companies reporting clearly on their diversity and inclusion policies, and encouragingly some companies also explain diversity initiatives which they have put in place.

4. Audit, Risk and Internal Controls

Audit

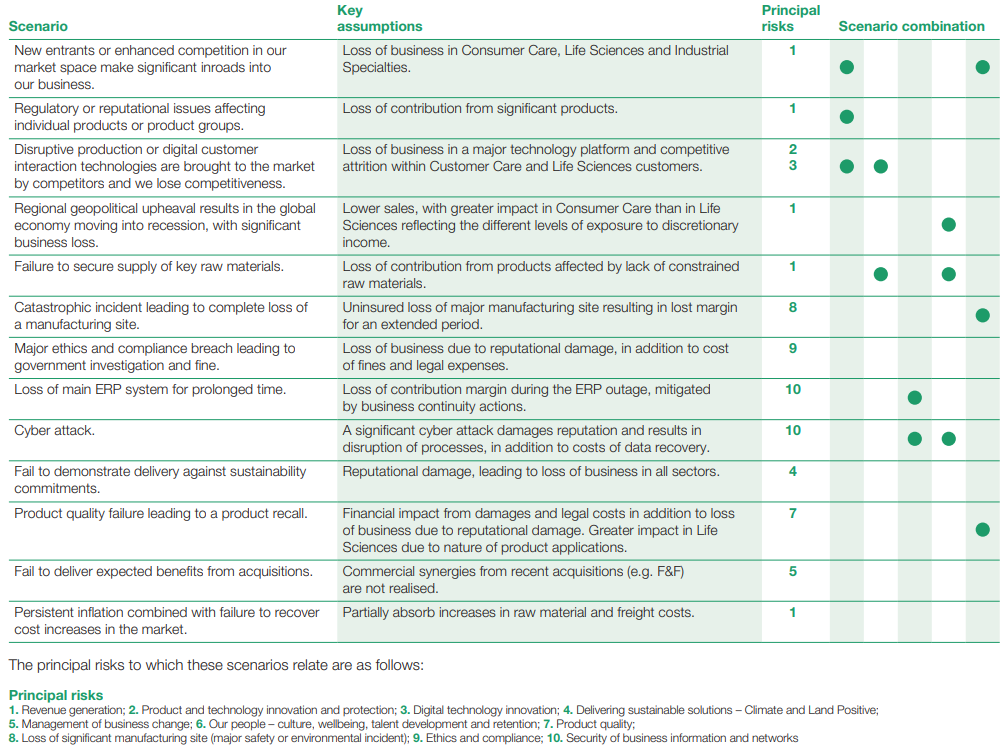

Provision 26: