The content on this page has been converted from PDF to HTML format using an artificial intelligence (AI) tool as part of our ongoing efforts to improve accessibility and usability of our publications. Note:

- No human verification has been conducted of the converted content.

- While we strive for accuracy errors or omissions may exist.

- This content is provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon as a definitive or authoritative source.

- For the official and verified version of the publication, refer to the original PDF document.

If you identify any inaccuracies or have concerns about the content, please contact us at [email protected].

Audit Quality Inspection Report May 2014: Ernst & Young LLP

Financial Reporting Council

The FRC is responsible for promoting high quality corporate governance and reporting to foster investment. We set the UK Corporate Governance and Stewardship Codes as well as UK standards for accounting, auditing and actuarial work. We represent UK interests in international standard-setting. We also monitor and take action to promote the quality of corporate reporting and auditing. We operate independent disciplinary arrangements for accountants and actuaries; and oversee the regulatory activities of the accountancy and actuarial professional bodies.

The FRC does not accept any liability to any party for any loss, damage or costs howsoever arising, whether directly or indirectly, whether in contract, tort or otherwise from any action or decision taken (or not taken) as a result of any person relying on or otherwise using this document or arising from any omission from it.

© The Financial Reporting Council Limited 2014 The Financial Reporting Council Limited is a company limited by guarantee. Registered in England number 2486368. Registered Office: 5th Floor, Aldwych House, 71-91 Aldwych, London WC2B 4HN.

1. Background information and key messages

1.1 Introduction

This report sets out the principal findings arising from the inspection of Ernst & Young LLP (“EY” or "the firm") carried out by the Audit Quality Review team of the Financial Reporting Council ("the FRC"), in respect of the year to 31 March 2014 (“the 2013/14 inspection"). We inspect EY annually. Our inspection was conducted in the period from April 2013 to January 2014 (referred to as "the time of our inspection"). The objectives of our work are set out in Appendix A.

Our inspection comprised reviews of individual audit engagements and a review of the firm's policies and procedures supporting audit quality.

We reviewed 16 audit engagements undertaken by the firm in our 2013/14 inspection. These related to FTSE 100, FTSE 250, other listed and other major public interest entities, with financial year ends between December 20111 and March 2013. Our reviews were selected on a risk basis, utilising a risk model; each review covered only selected aspects of the relevant audit.

Our responsibility is to monitor and assess the quality of the audit work performed by the UK firm. Accordingly, our reviews of group audits covered the planning and control of the audit by the group engagement team, including their evaluation of the adequacy of the work performed by component auditors, and selected aspects of other work performed by the UK firm at group and/or component level. Our reviews did not cover audit work at component level undertaken by other firms within or outside the firm's international network.

Our review of the firm's policies and procedures supporting audit quality covered the following areas:

- Tone at the top and internal communications

- Transparency report

- Independence and ethics

- Audit methodology, training and guidance

- Performance evaluation and other human resource matters

- Client risk assessment and acceptance/continuance

- Consultation and review

- Audit quality monitoring

- Other firm-wide matters

We exercise judgment in determining which findings to include in our public report on each inspection, taking into account their relative significance in relation to audit quality, both in the context of the individual inspection and in relation to any areas of particular focus in our overall inspection programme for the relevant year. Where appropriate, we have commented on themes arising or issues of a similar nature identified across more than one audit.

Further information on the scope of our work and the basis on which we report is set out in Appendix A.

All findings requiring action set out in this report, together with the firm's proposed action plan to address them, have been discussed with the firm. Appropriate action may have already been taken by the date of this report. The adequacy of the actions taken and planned will be reviewed during our next inspection.

The firm was invited to provide a response to this report for publication. The firm's response is set out in Appendix B.

We acknowledge the co-operation and assistance received from the partners and staff of EY in the conduct of our 2013/14 inspection.

1.2 Background information on the firm

Ernst & Young LLP is a UK limited liability partnership and the UK member firm of the EY global network of firms and EY Europe. EY Europe controls Ernst & Young LLP and the UK partners are also members of EY Europe. The UK firm is managed by a UK Board and the UK Country Managing Partner who has full authority to deal with the firm's general and operational management.

The firm operates through four service lines: Assurance, Advisory, Tax and Transactions Advisory Services. The UK Assurance practice has two principal business units, ‘Financial Services” (“FSO”) and 'UK & Ireland' (“UK&I”). It has 21 offices in the UK as well as offices in Jersey and Guernsey.

For the year ended 30 June 2013, the firm's turnover was £1,721 million, of which £507 million related to the Assurance service line. There were 571 partners in total, of whom 108 were authorised to sign audit reports, and 62 employees (audit directors) who were authorised to sign audit reports2.

We estimate that the firm audited 321 UK entities within the scope of independent inspection as at 31 December 2012. Of these entities, our records show that 121 had securities listed on the main market of the London Stock Exchange, including 12 FTSE 100 companies and 37 FTSE 250 companies.

The UK firm audits entities incorporated in Jersey and Guernsey whose securities are traded on a regulated market in the European Economic Area. These audits are inspected by us under separate arrangements agreed with the relevant regulatory bodies in those jurisdictions. The results of any reviews by us are included in this report. Our records show that, at the time of our inspection, the firm had 44 such audits, including 2 FTSE 100 companies and 5 FTSE 250 companies.

1.3 Overview

We focus in this report on matters where we believe improvements are required to safeguard and enhance audit quality. We set out our key messages to the firm in this regard in section 1.4. While this report is not intended to provide a balanced scorecard, we highlight certain matters which we believe contribute to audit quality, including the actions taken by the firm to address findings arising from our prior year inspection.

The firm places considerable emphasis on its overall systems of quality control and, in most areas, has appropriate policies and procedures in place for its size and the nature of its client base. Nevertheless, we have identified a number of areas where improvements are required to those policies and procedures, in particular those in relation to monitoring of and compliance with independence and ethics matters. These are set out in this report.

Our file review findings, as set out in section 2, largely relate to the application of the firm's procedures by audit personnel, whose work and judgments ultimately determine the quality of individual audits. In particular, four audits reviewed by us required significant improvement. Two of these were audits of entities where the company's general and financial management are located outside the UK (letterbox companies3). In each case insufficient audit procedures were performed to provide the group audit engagement partner with an appropriate basis on which to sign the group audit opinion. As a result of our focus on letterbox companies in the current cycle and the issues we have raised, the firm has significantly enhanced its guidance in this area and has provided specific, mandatory training for all partners and staff. We will test the effectiveness of this guidance during our next inspection cycle.

In response to our prior year findings, the firm has taken steps to achieve improvements and has emphasised the requirements in the relevant areas through training and communications to the audit practice. However, issues continued to arise in a number of these areas including revenue recognition, group auditing considerations, testing of IT controls and impairment of goodwill, as noted below. The firm should therefore review the effectiveness of its actions in these areas. In addition, we have raised similar concerns to those in the prior year regarding the impact on audit quality of resourcing challenges.

1.4 Key messages

The firm should pay particular attention to the following areas in order to enhance audit quality and safeguard auditor independence:

- Conduct a thorough analysis of the reasons for the increase in the number of audits requiring improvement and identify actions to enhance audit quality.

- Closely monitor the effectiveness of actions planned and implemented to manage resourcing challenges with a particular focus on the impact on audit quality.

- Improve the quality of audit evidence obtained and testing performed in those areas where we raised significant issues, through more rigorous review of audit procedures planned as well as the conduct of audit work.

- Ensure that the briefing and training provided in relation to the audit of "letterbox companies" is being appropriately applied in practice through internal quality monitoring.

- Reconsider how the work of specialists is integrated into the overall work of the audit team and provide further guidance on the assessment and follow-up of evidence obtained from specialists.

- Develop appropriate monitoring and follow-up procedures to ensure that independence issues identified by the systems and processes in place are appropriately addressed on a timely basis.

2. Principal findings

The comments below are based on our reviews of individual audits and the firm's policies and procedures supporting audit quality.

2.1 Reviews of individual audits

We reviewed and assessed the quality of selected aspects of 16 audits (2012/13: 14 audits, of which two were follow-up reviews of audits reviewed in our 2011/12 inspection) We did not conduct any follow-up or further reviews in the current inspection.

Six of the audits we reviewed (2012/13: 10) were performed to a good standard with limited improvements required and six audits (2012/13: one) required improvements. Four audits4 (2012/13: one) required significant improvements in relation to one or more of the following audit areas: group audit considerations particularly in relation to letterbox companies, going concern, intangible assets, IT controls testing and the audit of actuarial models and provisions. Further details are set out later in this section.

An audit is assessed as requiring significant improvements if we have significant concerns in relation to the sufficiency or quality of audit evidence or the appropriateness of significant audit judgments in the areas reviewed, or the implications of other matters considered to be individually or collectively significant. This assessment does not necessarily imply that an inappropriate audit opinion was issued.

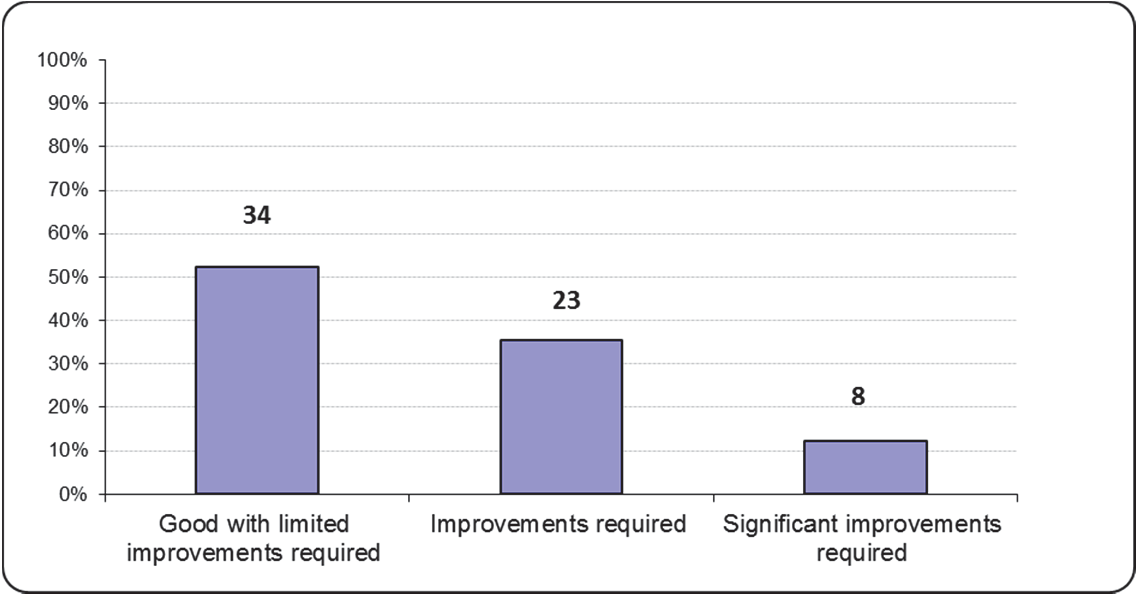

The bar chart below shows the percentage of the audits we reviewed in 2013/14 falling within each grade, with comparatives for 2012/13 and 2011/12. The number of audits within each grade is shown at the top of each bar.

Changes to the proportion of audits reviewed falling within each grade from year to year reflect a wide range of factors, which may include the size, complexity and risk of the individual audits selected for review and the scope of the individual reviews. For this reason, and given the sample sizes involved, changes in gradings from one year to the next are not necessarily indicative of any overall change in audit quality at the firm. In the bar chart below, we have therefore provided summary information over a longer period and, consequently, based on a larger number of audits. This shows the proportion of audits reviewed falling within each grade in the five years up to and including 2013/14. The number of audits within each grade is shown at the top of each bar.

Chart showing the proportion of audits reviewed falling within each grade over five years up to 2013/14. - Good with limited improvements required: 34 - Improvements required: 23 - Significant improvements required: 8

Findings in relation to audit evidence and judgments

Our reviews focused on the audit evidence and related judgments for material areas of the financial statements and areas of significant risk. We draw attention below to the following findings which the firm should ensure are addressed appropriately in future audits.

The significance of these findings in the context of an individual audit reviewed, and, therefore, the implications for our grading of that audit, will vary. However, whatever the implications for the specific audits reviewed, we nevertheless include the relevant findings in this report if we consider them important in the broader context of improving audit quality at the firm.

Revenue recognition

The audit of revenue was reviewed on eight audits. We identified issues on six audits including insufficient testing of controls over assertions relating to revenue on four audits. In two of the six audits, insufficient audit procedures were performed and insufficient evidence obtained to substantiate whether revenue had been recorded in the correct period. Analytical review procedures are frequently used to obtain substantive evidence in the audit of revenue. Weaknesses were identified in relation to aspects of the application of substantive analytical procedures in four of the six audits, including expectations either not being set or not being set with sufficient precision and without adequate corroboration of management explanations.

In six of the eight audits where revenue recognition was reviewed, we considered that there was insufficient evidence to support the conclusion that either: a) certain revenue streams did not give rise to a significant fraud risk; or b) the risk of fraud in relation to revenue recognition was not significant for any revenue stream. Weaknesses in the risk assessment relating to revenue increased the risk that the auditors might not identify a material misstatement of revenue in the financial statements due to fraud.

Group audit considerations

We reviewed group audit considerations on nine audits. In four audits, we identified issues with either the sufficiency of the group audit team's involvement in component auditors' risk assessments or the extent of their review of component auditors' work. In three audits we identified issues surrounding the scoping of the group audit. In one of these audits, the group team did not set the materiality level for the audit of a component; this was instead set by the component auditors, who selected a materiality level equal to overall group materiality, which we considered to be inappropriate.

Letterbox company audits

Four of the audits we reviewed were ‘letterbox companies'. In relation to two of the four audits, we concluded that significant improvements were required. In the first of these, the majority of the group audit work was effectively undertaken by a third country EY network firm (i.e. an EY firm unrelated to either the location of the group's head office or the location of its operations). There was insufficient evidence of the UK firm's supervision and direction at the planning stage of the group audit. There was, for example, no evidence of the team's involvement in the determination and allocation of component materiality levels or their involvement in or review of the inter-office instructions issued by the third country EY network firm. Further, the group audit team did not perform audit procedures on the consolidation, as required by Auditing Standards, nor was there evidence of any involvement of the UK firm in key audit areas for the UK component.

In the second of these audits, there was insufficient evidence of the UK partner taking responsibility for leading and supervising the group audit. The group audit was effectively undertaken in its entirety by the EY network firm in the country of the group's head office. The EY network firm performed all audit work relating to the balances in the group financial statements without adequate direct supervision by the UK firm and the group audit team did not perform audit procedures on the group consolidation, as required by Auditing Standards.

In three letterbox company audits there was insufficient consideration of the UK fit and proper requirements in relation to personnel from overseas EY network offices performing audit procedures directly for the UK firm. In two letterbox company audits we identified that the firm had not adequately reported to the Audit Committee information concerning audit team structures and personnel.

Quality of audit evidence

In three cases, in the absence of a clear explanation of the audit work performed it was not possible to understand the basis for the conclusions reached on certain key judgmental areas.

In one audit of an investment company, the majority of the investment portfolio consisted of unquoted equity instruments valued using discounted cash-flow models. There was insufficient evidence of the audit work performed on the valuation of the investment portfolio.

In two other audits, both entities in the insurance sector, there was insufficient evidence of the audit procedures performed relating to the actuarial and audit finalisation processes.

As a result of these issues, certain aspects of audit evidence were not included on the audit files and were therefore not subject to the firm's full quality control review procedures.

Testing of internal controls

We considered aspects of the audit team's work on internal controls in the majority of audits selected and in three audits identified issues with the overall controls approach adopted.

In one of these audits, we considered that the procedures performed to evaluate the controls operating at an individual site level were inadequate. The effectiveness of the central controls on which the group audit team relied depended on the site level controls operating effectively; however, they neither relied on testing performed by management's own team nor did they independently follow up or corroborate the findings of the site reports prepared by management's own team. Further, the attendance of the group audit team at only one site visit was insufficient for audit purposes.

In another of these audits, we identified a number of instances where the sample sizes chosen for testing controls differed from the planned testing portfolio and it was unclear that an appropriate strategy had been in place from the outset.

In the third of these audits, relating to an entity operating in the financial services sector, the group audit team concluded that certain controls were homogeneous and therefore operated in the same manner across regions and across entities on a global basis. As a result, for certain key controls, testing was limited to one sample which was allocated between the audit teams across a number of locations globally and on which the audit team in each location relied. Whilst these controls may have been consistently designed and implemented globally, there was insufficient evidence to conclude that they operated on a homogenous basis. The inputs to these controls, particularly manual elements, would not have been homogenous. As a result of this approach, we considered that the testing of controls performed was insufficient for reliance to be placed on them.

During the course of our discussions with the firm on the action plan in relation to this audit, a recently introduced global audit approach was drawn to our attention. The firm believes that where a suite of controls are subject to common control and are applied consistently in a number of locations globally, a single global sample may be selected for testing. It has yet to be demonstrated to us that this approach complies with Auditing Standards.

IT controls testing

We reviewed the audit of IT controls on four audits and identified issues in this area in each case. In two audits, testing one item was not sufficient to conclude as to whether certain access rights were appropriately segregated. In a further audit, there was insufficient evidence as to how the group audit team mitigated audit risks arising from the identification of inappropriate password controls and segregation of duties. Also, testing of IT general controls performed at an interim date was not updated appropriately to the balance sheet date. In the remaining audit, there was insufficient evidence that the audit team had established a basis for reliance on electronic audit evidence obtained from reports generated from IT systems. In addition, weaknesses were identified in relation to the audit procedures performed over the completeness of certain automatically generated reports.

Goodwill and other intangible assets

We reviewed the audit of goodwill or other intangible assets in seven of the audits we selected. On three audits issues were identified with the procedures performed to test impairment. In two of these audits, there was insufficient evidence of assessment of the reasonableness of the growth rates or other assumptions used, the reliability of the source data and the appropriateness of the methodologies adopted by management in their impairment review.

In one of these audits the group had significant intangible assets in the form of exploration and evaluation (E&E) licences. Insufficient audit evidence was obtained regarding additional amounts capitalised in relation to these licences, including those operated directly by the group and those operated by third parties. Further, the final valuation of acquired assets included a significant uplift to the value recorded in the books of the acquired entity. The audit team did not sufficiently challenge the appropriateness of the allocation of the fair value to assets acquired in a business combination; consequently, insufficient audit evidence was obtained that management's valuations were appropriate.

Going concern assessment

We assessed the quality of the firm's audit work in relation to the assessment of going concern on eight audits in our sample. In five audits, we identified issues in one or more of the following areas: insufficient assessment by the audit team of management's consideration of the going concern assumption; insufficient evidence of the consideration of key factors relevant to the assessment of going concern; inconsistencies with assumptions used by management in other areas, and inadequate disclosures in the financial statements.

In one of these audits there was insufficient evidence that the audit team had considered the likelihood of certain licences being renewed. The non-renewal of these licences could potentially have had a significant impact on the entity's ability to continue as a going concern. In a second audit, there was insufficient evidence of audit work being performed on an underwriting agreement for a rights issue fundamental to the going concern assessment. Furthermore, insufficient procedures were performed regarding the appropriateness of the disclosures in the financial statements of this entity relating to the going concern assumption.

Use of the work of Internal Audit

In two of the audits reviewed, the audit team obtained direct assistance from members of the entity's internal audit function. In one of these audits, the group audit team provided insufficient direct supervision of the work performed by the internal audit staff and relevant findings were reported through the head of internal audit, rather than directly to the EY group audit team. In both these audits, the group audit team did not appropriately confirm with the Audit Committee the relevant responsibilities of the internal audit staff and those of the external auditor.

Financial assets and liabilities

We reviewed the audit work on various classes of financial assets and financial liabilities in eight audits in our sample.

In two audits, both in the insurance sector, there was insufficient evidence of the approach and audit testing performed by the audit team's actuarial specialists, including the testing of actuarial models. In addition, in one of these audits there was insufficient evidence supporting the actuaries' assessment of both the individual and cumulative impact of the issues they identified during their review.

In two audits we identified issues in relation to the audit work performed on the fair valuation of derivative financial instruments. In one of these audits we considered that the audit team had performed insufficient testing of the most complex financial instruments where a significant input to fair value is not based on observable market data. In addition, the audit team had not conducted their work in this area in accordance with planned procedures. In the other audit, there was insufficient evidence that procedures performed at an interim date had been adequately updated to the balance sheet date.

In three other audits we identified issues in the audit of non-derivative financial assets and liabilities. In one of these audits, there was insufficient evidence that audit procedures performed at an interim date relating to cash balances were adequately updated to the balance sheet date. Further, controls identified and relied upon by the audit team did not address the relevant financial statement assertions relating to the cash balances.

Journals testing

In three audits, there was insufficient justification for the number of journals tested. In one of these audits, there was a lack of evidence that the audit team had appropriately identified and tested higher risk journals.

In a fourth audit, journal testing was performed by another network firm and there was no evidence of the group audit team's involvement in, or oversight of, this work.

Use of experts

In one audit, the planned approach included an audit of external investment property valuations to be undertaken by the firm's valuation specialists at the half-year and then repeated at year-end. There was no evidence that the audit team challenged management on the year-end valuations or followed up points raised by the firm's valuation specialists at the half-year.

Consideration of accounting policies

In two audits which we reviewed we identified issues in relation to the consideration of accounting policies adopted in the financial statements. In one of these audits the appropriateness of the company's accounting policy in relation to the transfer of a business of a subsidiary was not sufficiently challenged and it was unclear how the conclusion was reached that the company's accounting policy complied with IFRS. Further, the various accounting options and their impact did not appear to have been discussed with management or the Audit Committee. In the other case there was insufficient evidence that the audit team had considered the appropriateness of disclosures relating to certain litigation matters that may have met the definition of a provision under Accounting Standards. These matters had not been recognised as provisions in the group balance sheet and there was no disclosure of the obligation or the best estimate of the amount due.

Other findings

Materiality

We reviewed the basis on which the overall materiality level was set on each of the audits in our sample. In three audits, there was insufficient justification for the basis on which materiality had been set including, in one of these audits, an increase in the level from 1% of equity in the prior year to 2% in the current year.

Engagement Quality Control Reviewers

In two audits we identified matters which could impinge on the independence of the engagement quality control review (EQCR) partner. In one of these audits, the EQCR partner also performed the role of IFRS technical review partner. The role of the EQCR is to provide an objective evaluation of the significant judgments and conclusions made by the audit team. The performance of this dual role increased the risk that the relevant partner may not have been able to discharge the responsibilities of an EQCR partner independently and effectively.

Independence – non-audit services

In one audit, part of the fee arrangements agreed for non-audit services involved what was, in substance, a contingent fee. There was insufficient consideration of the threats arising from this arrangement or assessment of whether these could be reduced to an acceptable level. In a second audit, where non-audit fees exceeded the audit fee for the year, the audit engagement partner did not discuss the circumstances with the firm's Ethics Partner as required by Ethical Standards.

2.2 Review of the firm's policies and procedures

The firm's policies and procedures are largely developed globally and are implemented at an EY Europe level. The UK firm commits significant resources to their development at both a global and regional level; particularly in relation to independence compliance and monitoring procedures, risk assessment, audit training and technical communications, and monitoring the quality of audit engagements.

Improvements made during the year

Certain prior year findings have been satisfactorily addressed by the firm in the current year. In particular, improvements have been made in relation to partner appraisals which are now conducted and evidenced on a more consistent basis. Enhanced guidance was produced on the partner evaluation and remuneration process, with mandatory requirements in certain areas where we had raised concerns in prior years. Briefing sessions were also held with partners to clarify key messages.

As in prior years, a list of “hot topics” was issued to all audit staff summarising key areas of focus relating to audit quality for 2013 year end audits. The list of hot topics formed part of the firm's response to our prior year findings and included key messages on the planning and review of audit work, identification and response to significant risks and controls testing, as well as the assessment of independence threats and safeguards. These areas were all included as key components of the firm's mandatory classroom training during the year. Technical alerts were also issued as appropriate.

Prior year findings not adequately addressed

Audit of IT controls

We concluded in the prior year that the firm should establish through its internal quality reviews whether improvements are needed to the firm's guidance and training on the audit of IT controls. We saw no evidence that greater emphasis was placed on IT controls in the course of the firm's 2013 audit quality monitoring. In the current year the firm's internal reviews did not identify any IT findings; however, we identified aspects of the audit of IT systems and controls (set out in Current Findings below) which are not adequately addressed in the firm's training and/or guidance.

Sufficiency of resources

We also concluded in the prior year that the firm should review its procedures to ensure additional resources are made available to support partners and staff in exceptionally challenging circumstances. While audit teams were encouraged during the firm's mandatory training in 2013 to ask for help in challenging circumstances and a process of monthly calls was established, there was no evidence that EY's operational management had carried out any analysis to understand why this had arisen as an issue in prior years and what actions should be taken to prevent it from recurring.

Partner performance evaluation and remuneration

In general, partner appraisals were conducted and evidenced on a more consistent basis this year. However, the support for Quality Ratings still requires improvement. Objective assessments of quality arise from internal and external quality reviews, including our own reviews. Partner appraisals should consistently record whether the partner was subject to any of these processes, the stage that the review has reached at the time of the appraisal process and the expected outcome. The results of incomplete processes should be reflected in the following year. Appraisers should ensure that other attestations of quality are supported by independent evidence.

The firm's remuneration policy is designed to take account of each partner's Quality Rating in setting remuneration and we have seen evidence of this in most cases. However, we found that the impact of a reduced Quality Rating can still be undermined by the overall increase in remuneration as a result of other factors.

Although there was a considerable improvement in adherence to the completion timetable, a number of partner appraisals were completed up to three weeks after the firm's deadline. Furthermore, despite the appraisal process notes and instructions clearly stating that credit should not be sought for sales of non-audit services to audit clients, one partner and one candidate for partner admission made reference to their success in achieving such sales and there was no evidence of this being challenged by their superiors. This indicates that there is still a perception among certain partners that they will be rewarded for non-audit sales to their own audit clients.

Performance evaluation for senior staff

An appraisal system which incorporates specific quality measures has been put in place for senior staff. Improvements are, however, required to the evidence supporting the quality assessment based on the results of internal and external quality reviews.

Current year findings

In our 2013/14 inspection we identified certain further areas where improvements to the firm's policies and procedures are required, as set out below, which need to be addressed. These are set out below.

Tone at the top

Sufficiency of resources

We found evidence during our inspection that had implications for the sufficiency of resources within the firm. The firm's staff survey highlighted that only a third of staff in Assurance, compared to half of the staff across the firm as a whole, agreed with the statement that 'I have the time I need to deliver quality work'. The firm's Audit Quality Monitoring (AQM) report noted in relation to staff allocation that limited people resources had been cited as a key concern among professionals at all levels. The Assurance Leadership Team also noted in the year that AQM results were only marginally up on the prior year if at all, and expressed concern about the impact of utilisation on quality. This is not inconsistent with the findings of our own file reviews. In response to our observations above the firm has informed us that the Assurance Leadership Team's focus on utilisation in the current year did not identify any increases that were of significant concern. In this context, we were provided with a high-level summary of management's utilisation data. Also, we understand that a recruitment campaign was initiated to maintain resource levels in future.

Independence and ethics

Financial interest in an audited entity

We were informed by the firm that there was a breach of the firm's ethical policies, relating to an equity partner's financial interests in one of the firm's audited entities. This related to a senior partner, who purchased shares in an investment fund which was audited by the firm. In November 2013, in the particular circumstances of this case, the FRC launched an Accountancy Scheme investigation into the conduct of the firm in this matter.

Personal independence monitoring

The firm requires investments held by partners and staff, together with those held by immediate family members, to be registered promptly on the Global Monitoring System (GMS). When individuals are identified as holding prohibited investments GMS requires their disposal. There was, however, until recently, no formal escalation process if such investments were not promptly disposed of by the individuals concerned. In addition, because the updating of GMS and related systems depends on certain manual processes which are not sufficiently monitored, there is a risk that prohibited investments and exceptions are not being identified on a timely basis.

Each year the firm carries out an independence confirmation process for all partners and professional staff. In addition, the firm tests the accuracy of the partners' and managers' financial interests data as recorded in GMS on a sample basis. Any omissions or errors by partners, including those that resulted in a failure to dispose of holdings in prohibited entities, are subject to a financial penalty. The firm requires all partners and managers in the sample to provide supporting documentation for their investments as part of the testing process. We were informed, however, that in one case supporting documentation was not supplied by a partner and this was not followed up.

Until recently, there was no formal escalation process in place beyond the Ethics Partner to deal with continued non-compliance by partners in relation to matters arising from either the independence confirmation process or the personal independence testing process. An escalation process has recently been introduced for independence matters identified as part of the personal independence testing. We will review this during our next inspection cycle.

Non-audit services and fees

We noted one case where the approval for a non-audit service provided to an audited entity was obtained retrospectively. In addition, an engagement letter was not sent until after the work was complete. We note also that the firm undertook its own monitoring in this area and identified three other instances where engagements had commenced prior to obtaining the necessary approval to provide the service.

Our review also identified instances where non-audit services were approved with insufficient evidence that threats to auditor independence and appropriate safeguards had been adequately considered by the audit team. Although all teams are required to complete the firm's standard process for approving non-audit services, this is not consistently followed. Certain procedures adopted in practice do not ensure evidence that independence threats arising and the related safeguards applied have been considered and addressed appropriately. The standard approval process should be followed for all audited entities and evidence of proper consideration of threats and safeguards should be required.

Furthermore, the firm cannot readily identify total non-audit fees for an audited entity without requesting the data from each audit team. This results in an increased risk that audit teams may not be in a position to monitor such fees effectively.

Partner and staff rotation – length of involvement

For partners and other individuals subject to rotation the firm records the number of year-ends of involvement in an audit, rather than the length of time involved as required by the Ethical Standards. This matter came to our attention as a result of an audit we reviewed where the firm had decided to exclude the audit engagement partner's initial year of involvement for the purposes of monitoring rotation requirements as the entity's business had not started trading until the following year. There was, however, an Initial Public Offering during this initial year of involvement.

The exclusion of this initial year does not comply with Ethical Standards which only allow an extension to the audit engagement partner's length of time on listed entities at the end of a five year period of tenure, when required by the Audit Committee (or equivalent) to safeguard the quality of the audit. However, no breach of the rotation requirements in Ethical Standards occurred as the firm acted promptly when we identified this matter. A new audit engagement partner was then appointed prior to the relevant year-end.

Retired partner joining an audited entity

Ethical Standards require the firm to resign as auditor if a partner leaves the firm and is appointed as a director or to a key management position with an audited entity, having previously acted as the audit engagement partner, engagement quality control reviewer, a key partner or a partner in the chain of command at any time in the two years prior to this appointment. The firm does not always retain the information supporting the decision as to whether EY should resign as auditor in situations where retired partners join an audited entity within two years of leaving the firm.

Audit pricing

The firm has issued recent guidance which indicated that if the firm could not achieve the required fee increases for an audited entity then it could agree to various 'concessions' instead including asking for "more work (e.g. specialist work resulting from regulatory change)". This is contrary to the Ethical Standards which require the audit engagement partner to ensure that audit fees are not influenced or determined by the provision of non-audit services to the audited entity. Other suggestions in the guidance include the partner and audit team spending less time in meetings with the audited entity and having fewer of them, and the audit team being on site for less time. There was no corresponding guidance provided that suggested how this could be achieved without having a detrimental impact on audit quality.

Audit methodology, training and guidance

Materiality for Emerging Growth Entities

The firm's audit methodology, which is developed and updated by EY Global, allows the materiality of an entity which is considered an Emerging Growth Entity (EGE) to be set at a significantly higher percentage of equity than an established, listed entity. However, there is no corresponding guidance to appropriately adjust performance materiality for an EGE given that these entities are likely to be assessed as a higher risk audit than a comparatively established entity. As a consequence performance materiality may be set at a higher level for an EGE where the risk of material misstatement may be greater due to the nature of the entity.

Assessment of IT risk and complexity

Audit teams are required to assess how IT affects the audit strategy and consider the complexity of the IT environment each year. This is, however, not necessarily performed by an IT specialist even if the IT environment is expected to be complex. Accordingly, there is a risk that audit teams do not fully understand the nature and/or extent of any planned IT changes at the application or infrastructure level. The firm should revisit the requirements for interaction between the audit team and IT specialists for complex IT environments to ensure that the guidance to related IT audit strategy is considered appropriately.

While IT audit specialists receive formal training on the testing of IT application controls, the same extent of training is not provided to other audit staff who are regularly involved in such testing. We identified examples of inappropriate IT application controls testing by non-IT audit staff, due to their not having adequately assessed the characteristics of the controls they are testing and the related transactions and processes. The firm should ensure a consistent approach to the testing of IT application controls by requiring all relevant non IT audit staff to have appropriate IT training and experience.

IT systems and controls testing

The firm's audit methodology provides several approaches and testing techniques to assess the reliability of system generated information. Although relevant training was provided in the year, there is insufficient guidance explaining how procedures, including sample sizes, may vary with the complexity of such information. The firm should expand its guidance to ensure a more consistent approach to testing system generated information, including sample sizes and the distinction between standard and bespoke reports.

The firm's audit methodology requires IT audit teams to determine any follow-up procedures required at the year-end where controls testing has been performed at an interim date. However, there are no standard procedures clarifying the extent of additional audit evidence required to update interim testing to the balance sheet date.

Audit Quality Monitoring (AQM)

Recurring findings in AQM reviews

A number of the key findings identified by the firm's Audit Quality Monitoring (“AQM”) process continue to be recurring findings from earlier years. The firm should establish the root cause for these recurring findings and identify why any previous remedial action has not been effective, prior to determining what further steps to take to address these matters effectively.

File reviews

EQCRs are not formally notified of the outcome of AQM reviews of audits in their portfolios. Given that their role is specifically focussed on audit quality, EQCRs should always be informed of the relevant results.

Three offices received significantly fewer audits graded 1 in the firm's AQM process compared to the firm's overall results. However there was no impact on the quality ratings of the partners in charge of audit quality for these offices.

Firm-wide processes

The firm opted to review most firm-wide processes on a triennial basis, following a full review in the 2012 AQM. In the 2013 UK AQM testing was only performed for staff allocation procedures and certain areas relating to audited entities included in the AQM reviews. This follows the introduction of an EY Europe-wide rotational programme to review all countries and their offices at least once every three years to assess the adequacy of their policies and procedures.

If a cyclical approach is adopted, key firm-wide procedures should be tested every year in accordance with the UK Audit Regulations & Guidance.

Transparency report

We reviewed the firm's transparency report for the year to 30 June 2013, which was published in October 2013, to assess whether the information in the report was consistent with our understanding of the firm's quality control and independence procedures. Except for the matters set out below, we did not identify any inconsistencies with our understanding of the firm's quality control and independence procedures.

We could not understand how the firm was able to state in its 2013 Transparency Report that its systems of quality control were operating effectively based on an annual review given that no review of the majority of firm-wide processes had taken place during the year as indicated in the AQM section above.

The Transparency Report includes certain statements which are not consistent with our prior year report on the firm. The Transparency Report includes the statement that “The FRC's report recognises our emphasis on audit quality;...” However the FRC's report states that “The firm places considerable emphasis on its overall systems of quality control and, in most areas, has appropriate policies and procedures in place for its size and the nature of its client base". We do not consider an 'emphasis on audit quality' to be the same as an 'emphasis on its overall systems of quality control'.

The Transparency Report also includes the statement that "The FRC's report on EY highlights an improvement in audit equality [sic].” Notwithstanding the error in using 'equality' rather than 'quality', this statement was incomplete as the FRC report was referring to individual audits reviewed rather than the firm as a whole.

Other matters

Audit reports - ISA 700 (Revised)

The firm has issued a template audit report and provided guidance and training on the requirements of the revised standard and matters relevant for practical application. The firm believes that as responsibility for the final report remains with the respective audit engagement partner, a mandatory review by the firm's central technical departments is not necessary, particularly as the rationale behind the changes to ISA 700 was to minimise the use of boilerplate audit reports in favour of those that are specific to the entity being audited. We will review the application of this policy during our next inspection cycle to ensure that it meets the objectives of the changes in the Standard.

Andrew Jones Director Audit Quality Review FRC Conduct Division May 2014

Appendix A – Objectives, scope and basis of reporting

Scope and objectives

The overall objective of our work is to monitor and promote improvements in the quality of auditing in the UK as part of our work, we monitor compliance with the regulatory framework for auditing, including the Auditing Standards, Ethical Standards and Quality Control Standards for auditors issued by the FRC and other requirements under the Audit Regulations issued by the relevant professional bodies. The standards referred to in this report are those effective at the time of our inspection. In relation to our reviews of individual audits, these effective at the time the relevant audit was undertaken.

Our reviews of individual audit engagements and the firm's policies and procedures supporting audit quality cover, but are not restricted to, the firm's compliance with the requirements of relevant standards and other aspects of the regulatory framework. Our reviews place emphasis on the appropriateness of key audit judgments made in reaching the audit opinion together with the sufficiency and appropriateness of the audit evidence obtained. We also assess the extent to which the firm has addressed the findings arising from our previous inspection.

We seek to identify areas where improvements are, in our view, needed in order to safeguard audit quality and/or comply with regulatory requirements and to agree an action plan with the firm designed to achieve these improvements. Accordingly, our reports place greater emphasis on weaknesses identified which require action by the firm than areas of strength and are not intended to be a balanced scorecard or rating tool.

Our inspection was not designed to identify all weaknesses which may result in the deeming and/or implementation of the firm's policies and procedures supporting audit quality or in relation to the performance of the individual audit engagements selected for review and cannot be relied upon for this purpose.

The professional accountancy bodies in the UK register firms to conduct audit work. Their monitoring units are responsible for monitoring the quality of audit engagements falling outside the scope of independent inspection, but within the scope of audit regulation in the UK. Their work, which is overseen by the FRC, covers audits of UK incorporated companies and certain other entities which do not have any securities listed on the main market of the London Stock Exchange and whose financial condition is not otherwise considered to be of major public interest. All matters raised in this report are based solely on the work which we carried out for the purposes of our inspection.

Basis of reporting

We exercise judgment in determining those findings which it is appropriate to include in our public report on each inspection, taking into account their relative significance in relation to audit quality, in the context of both the individual inspection and any areas of particular focus in our overall inspection programme for the year. Where appropriate, we have commented on themes arising or issues of a similar nature identified across more than one audit.

While our public reports seek to provide useful information for interested parties, they do not provide a comprehensive basis for assessing the comparative merits of individual firms. The findings reported for each firm in any one year reflect a wide range of factors, including the number, size and complexity of the individual audits selected for review which, in turn, reflects the firms' client base. An issue reported in relation to a particular firm may therefore apply equally to other firms without having arisen in the course of our inspection fieldwork at those other firms in the relevant year. Also, only a small sample of audits is selected for review at each firm and the findings may therefore not be representative of the overall quality of each firm's audit work.

We also issue confidential reports on individual audits reviewed during an inspection. While these reports are addressed to the relevant audit engagement partner or director, they are copied to the chair of the relevant entity's audit committee (or equivalent body).

The fieldwork at each firm is completed at different times during the year and rigorous quality control procedures are applied. These procedures include a peer review process at staff level and a final review by independent non-executives who approve the issue of all reports. These processes are designed to ensure both a high quality of reporting and that a consistent approach is adopted across all inspections.

Purpose of this report

This report has been prepared for general information only. The information in this report does not constitute professional advice and should not be acted upon without obtaining specific professional advice.

To the full extent permitted by law, the FRC and its employees and agents accept no liability and disclaim all responsibility for the consequences of anyone acting or refraining from acting in reliance on the information contained in this report or for any decision based on it.

Appendix B – Firm's response

The firm's response is on the following page

Ernst & Young LLP 1 More London Place London SE1 2AF Tel: +44 207 951 2000 Fax: + 44 207 951 1345 ey.com

16 May 2014

Dear Mr Jones

FRC Public Report on the 2013/14 Inspection of Ernst & Young LLP

We welcome the opportunity to respond to the FRC's report. We share with the FRC a common objective of promoting confidence in UK capital markets by a continuous focus on audit quality. We continue to invest in our business to achieve that.

As the FRC's public report shows, most of the gradings allocated by your inspectors to our audits in the prior year were in the FRC's top category. We were therefore disappointed that the current year gradings were not as positive as there have been no material changes in our audit practice. However, as the report points out in Section 2.1, a wide range of factors can influence your inspectors' ratings each year.

We also note, as you highlight in the above Section, that the change in gradings is not necessarily indicative of any overall change in audit quality at our firm. Nevertheless, we have already taken actions to address specific findings, such as those in relation to letterbox companies which had a major impact on our gradings this year. We have initiated a detailed review of the results of the inspection and will take appropriate additional actions in response to the findings.

Your observations on the audits inspected have also been discussed with representatives of the companies concerned.

We always gain benefits from an independent perspective and thank you for your work.

Yours sincerely

Hywel Ball UK Head of Audit

The UK firm Ernst & Young LLP is a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC300001 and is a member firm of Ernst & Young Global Limited. A list of members' names is available for inspection at 1 More London Place, London SE1 2AF, the firm's principal place of business and registered office.

Financial Reporting Council 5th Floor, Aldwych House 71-91 Aldwych London WC2B 4HN +44 (0)20 7492 2300 www.frc.org.uk

Footnotes

-

One December 2011 year-end audit with listed debt was reviewed. We conducted the planning for this review at the end of 2012/13 and completed the work in 2013/14. ↩

-

As disclosed in the annual return to the ICAEW as at 31 May 2013. ↩

-

Letterbox companies are those groups or companies that have little more than a registered office in their country of registration, with management and most activities being based elsewhere. In such situations, the auditor is usually based in the country of legal registration, rather than where management is based. ↩

-

One of these four was a December 2011 year-end audit with listed debt. We conducted the planning for this review at the end of 2012/13 and completed the work in 2013/14. ↩